Ấn Độ muốn phá vỡ thế độc quyền đất hiếm của Trung Quốc nhưng đối mặt nhiều thách thức

-

Trung Quốc hiện kiểm soát 69% sản lượng đất hiếm toàn cầu, và cùng Myanmar và Úc chiếm đến 80% thị phần thế giới. Ấn Độ nắm khoảng 6% trữ lượng toàn cầu nhưng chỉ chiếm 1% sản lượng do sản xuất chỉ đạt 2.900 tấn/năm trong hơn một thập kỷ qua.

-

Để phá thế phụ thuộc, Ấn Độ đang đẩy mạnh sản xuất nội địa và mở rộng hợp tác quốc tế với Mỹ, Oman, Việt Nam, Sri Lanka và Bangladesh.

-

Nhật Bản là hình mẫu thành công khi giảm phụ thuộc vào Trung Quốc xuống còn 60% nhờ hợp tác dài hạn với Lynas (Úc).

-

Những trở ngại lớn của Ấn Độ bao gồm: thiếu công nghệ tách – tinh chế phức tạp, thiếu đất hiếm nặng (dysprosium, terbium), tài nguyên chủ yếu là cát ven biển có hàm lượng thấp.

-

IREL, doanh nghiệp nhà nước, hiện là đơn vị duy nhất khai thác đất hiếm tại Ấn Độ, nhưng phần lớn vẫn tập trung sản xuất titanium từ ilmenite.

-

Dự án thí điểm sản xuất 1.500 tấn nam châm đất hiếm được cấp ngân sách Rs 1.000 crore (≈ 119 triệu USD), chỉ đáp ứng 5% nhu cầu nội địa (30.000 tấn/năm). Trong đó, IREL cung ứng khoảng 500 tấn nguyên liệu.

-

GSI đã khảo sát 51 địa điểm tại Rajasthan, nhưng chỉ có 3 nơi được xác định có tiềm năng neodymium – đều mới ở giai đoạn thăm dò ban đầu (G4).

-

Các rào cản bao gồm: khó khăn trong cấp phép khai thác, quy định bảo vệ môi trường, rừng và khu dân cư.

-

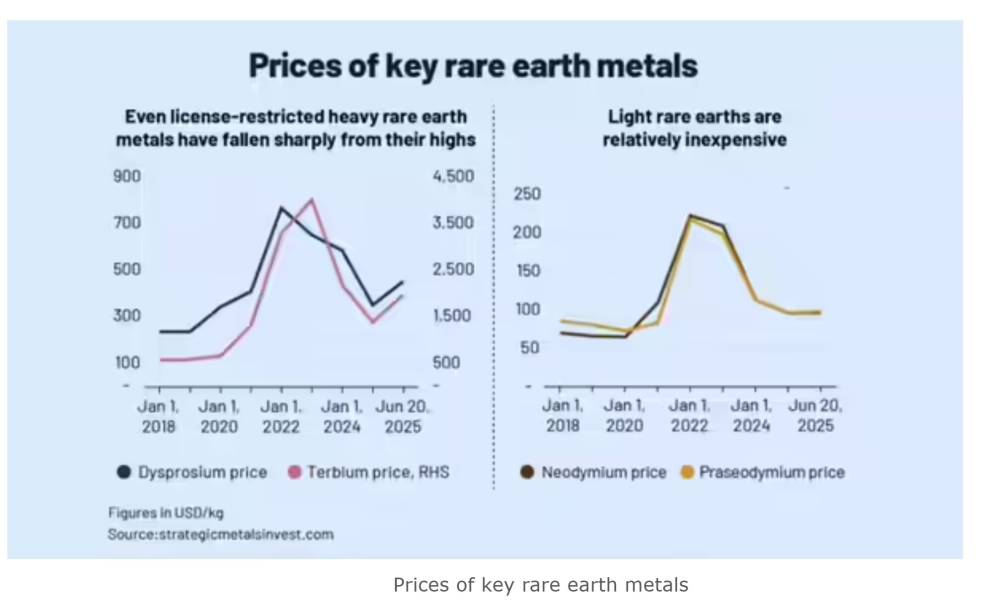

Giá đất hiếm toàn cầu giảm sâu khiến sản xuất trong nước không cạnh tranh được: nhập khẩu 53.700 tấn trong FY25 chỉ tiêu tốn Rs 1.744 crore (≈ 207 triệu USD), trong khi sản xuất nội địa 1.500 tấn cần đầu tư Rs 1.000 crore (≈ 119 triệu USD).

-

Tăng nhập khẩu 88% trong FY25 được cho là chiến lược dự trữ trước nguy cơ Trung Quốc siết xuất khẩu.

📌 Ấn Độ nắm 6% trữ lượng đất hiếm toàn cầu nhưng sản lượng chỉ chiếm 1%. Dự án sản xuất nội địa 1.500 tấn với vốn đầu tư Rs 1.000 crore (≈ 119 triệu USD) chỉ đáp ứng 5% nhu cầu, trong khi nhập khẩu cùng kỳ đạt 53.700 tấn với chi phí Rs 1.744 crore (≈ 207 triệu USD). Khó khăn chính gồm kỹ thuật, tài nguyên hạn chế và hiệu quả kinh tế thấp. Ấn Độ cần hợp tác quốc tế và đổi mới công nghệ để định vị thành nguồn thay thế Trung Quốc.

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/indias-bold-but-difficult-mission-why-countering-chinas-rare-earth-magnets-monopoly-wont-be-easy-major-roadblocks-ahead/articleshow/122231140.cms

Bold, but difficult mission! How India wants to counter China’s rare earth magnets monopoly - explained

TOI Business Desk / TIMESOFINDIA.COM / Updated: Jul 04, 2025, 11:32 IST

China's dominance in rare earth metals poses challenges for India, which seeks to establish a domestic production chain. Despite holding 6% of global deposits, India's output remains low due to technical and economic hurdles.

Did you know that China dominates the world’s rare earth metals and minerals supply? It’s a fact that the world’s second largest economy is exploiting to the fullest, increasingly so in view of the tariff war unleashed by US President Donald Trump.

In the global context, China dominates rare earth production with 69% share. The United States contributes 12%, whilst Myanmar holds 11% and Australia maintains 5%. Given Myanmar's strong economic and political alignment with China, their combined control extends to 80% of worldwide production.

Japan has successfully reduced its Chinese dependence to 60% through long-term agreements with Australia's Lynas Corporation, shifting from its previous near-total reliance on Chinese supplies.

India’s neighbour has also blocked supply of rare earth magnets to India, a situation that could hit the Indian industry. Acknowledging its extreme dependence on China, India has over the years moved to work out a solution – both through plans for domestic production and tie-ups with other countries.

India’s Rare Earth Roadblocks

As India embarks on a plan for domestic production of rare earth magnets, it is looking to enter a sophisticated technological arena currently controlled by a select few international manufacturers.

The initiative, supported by government funding and strategic planning, is ambitious yet complex.

Take the case of neodymium magnets – despite their small size, they are crucial components powering contemporary technology – from EVs and wind energy systems to mobile devices and defence equipment.

The manufacturing process requires specific combinations of light rare earth elements including neodymium and praseodymium, along with trace amounts of heavy rare earths such as dysprosium and terbium – materials that present significant challenges in both procurement and processing.

The development of an end-to-end domestic supply chain for rare earth magnets in India faces significant challenges as listed in an ET report, and finding solutions to these obstacles presents considerable difficulty.

Hurdle: Where are the mineral deposits?

India currently produces approximately 2.900 tons of rare earths, consisting entirely of light rare earths, with a notable absence of essential heavy rare earths.

India's primary rare earth deposits are found in coastal beach sands, with typically low mineral content. A recent finding in a Gujarat tribal village was finally found to be ultra-fine, micron-sized particles, rendering extraction both technically challenging and financially unfeasible.

The Geological Survey of India (GSI) has redirected its exploration efforts inland, particularly towards Rajasthan, though no substantial deposits of magnet-grade rare earths have been verified yet.

-

GSI has investigated 51 locations in the past four years, with 16 surveys conducted in FY25, increasing from 10 in FY22.

-

All these sites are situated in Rajasthan, indicating a strategic move away from coastal regions.

-

The outcomes have been limited, with only three locations – examined in FY22 and FY23 – identified for neodymium and related rare earths including dysprosium.

-

These sites remain at the G4 exploration phase (preliminary reconnaissance).

-

Ladi Ka Bas in Rajasthan is the sole site progressed to G2 level, though GSI has not explicitly confirmed the presence of magnet metals there.

Who will extract the rare earths?

IREL (India) Ltd, operating under the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), is the exclusive producer of rare earth elements in India. This public sector enterprise maintains the country's monopoly in rare earth production.

The organisation extracts rare earths as a secondary product whilst mining beach sand, specifically from monazite, which is classified as a radioactive mineral and falls under atomic energy regulations.

To establish an effective magnet supply chain, India requires comprehensive integration across various sectors including mining, separation, refining, materials science and magnet production. Currently, the country lacks these capabilities at a substantial scale.

India’s production strategy

The Department of Atomic Energy and Ministry of Heavy Industries (MHI) are in the final stages of developing a production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for rare earth magnets. The initiative, allocated Rs 1.000 crore (≈ 119 triệu USD), targets domestic production of 1.500 tonnes of rare earth magnets – just 5% of India’s projected requirement of 30.000 tonnes. IREL's contribution will be around 500 tonnes of raw material.

IREL’s core business remains focused on ilmenite, which generates substantial revenue through titanium dioxide pigment production. Rare earth metals are a secondary focus and still at a nascent stage.

In collaboration with BARC (Bhabha Atomic Research Centre), IREL has begun developing samarium-cobalt magnets for the defence sector. Prime Minister Modi inaugurated a pilot facility; deliveries are being evaluated.

IREL’s annual report highlights a critical challenge: “Availability of limited processing technologies and knowhow on rare earths other than China.”

India’s Rare Earth Production

-

India holds around 6% of worldwide rare earth deposits, yet its production stayed flat at 2.900 tonnes (2012–2024), about 1% of global output.

-

India’s rare earth elements mainly come from monazite in coastal sands – low yield, low return.

-

The Orissa Sands Complex processes 7,5 million tonnes of sand/year, producing 600.000 tonnes of industrial minerals, with few magnet metals.

-

IREL also operates in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, with combined output still just 2.900 tonnes/year.

-

Challenges include delayed permits, environmental approvals, CRZ restrictions, forestry issues, and population displacement.

-

Valuable deposits found in Odisha’s Puri district remain in limbo due to mining authorisation issues.

Price vs Economic Viability Challenge

Rare earth prices have fallen sharply. Lynas, the largest non-China neodymium producer, saw profits plummet: from 157 triệu USD (H1 FY22) to 5,9 triệu USD (H1 FY25).

-

India’s rare earth magnet imports surged 88% in FY25 to 53.700 tonnes.

-

But import value rose only 5% to Rs 1.744 crore (≈ 207 triệu USD), showing rare earths remain cheap despite high demand.

-

This makes domestic production uneconomical: producing 1.500 tonnes for Rs 1.000 crore (≈ 119 triệu USD) is more costly than importing 53.700 tonnes for Rs 1.744 crore.

-

Viability only improves if production scales up and becomes cost-efficient.

What’s the way ahead?

India’s FY25 import surge appears strategic — stockpiling in case of Chinese export curbs. Industrial sectors likely secured inventory, explaining their calm.

India’s rare earth bottleneck lies in technical and financial limits, not intent. The country has reduced royalty to 1% and initiated auctions since 2023. However, sustained investment, exploration, international partnerships, and regulatory reform will be essential for success in the coming years.

Thảo luận

Follow Us

Tin phổ biến