AI bản quyền

View All

-

Craig Scroggie, CEO NextDC (tập đoàn trung tâm dữ liệu lớn nhất Úc), cho rằng thay đổi luật bản quyền để hỗ trợ AI có thể thu hút thêm hàng tỷ USD đầu tư từ Microsoft và Google.

-

Ông nhấn mạnh: “Nếu luật bản quyền rõ ràng, đặc biệt về text và data mining, sẽ mở khóa một làn sóng nhu cầu mới trong đào tạo AI và thúc đẩy xây dựng hạ tầng kỹ thuật số.”

-

Microsoft và Google trong báo cáo gửi chính phủ đều khẳng định sẵn sàng “đầu tư thêm hàng tỷ USD” nếu có sự chắc chắn về luật bản quyền.

-

Microsoft đề xuất sửa đổi Đạo luật Bản quyền để cho phép huấn luyện mô hình AI (như ChatGPT) và bảo vệ bản quyền cho sản phẩm do AI tạo ra.

-

Google cảnh báo “innovation chill” – sự ngưng trệ đổi mới – do thiếu quy định về text/data mining và mơ hồ trong thuế trung tâm dữ liệu.

-

Tại Economic Reform Roundtable, Scott Farquhar (Atlassian, Tech Council of Australia) đề xuất nới lỏng luật để hỗ trợ startup AI và thu hút trung tâm dữ liệu quốc tế.

-

Đề xuất gây phản ứng mạnh từ truyền thông, ngành âm nhạc và một số chuyên gia AI, phản đối “ngoại lệ fair dealing” vì lo ngại xói mòn quyền lợi tác giả.

-

Bevan Slattery (người sáng lập NextDC) chỉ trích ngành công nghệ “đạo đức giả”, thách thức các công ty mở toàn bộ codebase của mình nếu muốn nới luật.

-

Một nhà điều hành trung tâm dữ liệu khác tiết lộ khách hàng lớn (big tech) lo sợ luật bản quyền Úc có thể làm tăng chi phí hoặc gánh nặng tuân thủ, dù chưa thấy rút vốn.

-

NextDC công bố báo cáo tài chính cả năm, cho thấy nhu cầu dịch vụ AI đẩy tăng lợi nhuận và cổ phiếu công ty bùng nổ.

-

Scroggie đề xuất giải pháp: mọi nội dung công khai nên được phép dùng cho huấn luyện AI, còn nội dung sau paywall thì cần cơ chế trả phí thỏa thuận với chủ bản quyền.

-

News Corp phản bác: “Đạo luật Bản quyền hiện tại đã bảo đảm quyền lợi ngành sáng tạo và không cần thay đổi.”

📌 Tranh luận về luật bản quyền đang trở thành tâm điểm trong chiến lược AI tại Úc. NextDC khẳng định chỉ cần sửa đổi nhỏ cũng có thể hút thêm hàng tỷ USD từ Microsoft và Google cho trung tâm dữ liệu, trong khi Google cảnh báo nguy cơ “innovation chill” nghĩa là sự đổi mới bị kìm hãm hoặc chậm lại do môi trường pháp lý. Tuy nhiên, ngành truyền thông và âm nhạc phản đối gay gắt, cho rằng khung pháp lý hiện tại đã đủ bảo vệ quyền lợi tác giả. Kết quả cải cách sẽ quyết định liệu Úc có trở thành điểm đến hàng đầu cho đầu tư AI toàn cầu.

https://www.afr.com/technology/copyright-reform-would-unleash-billions-in-ai-investment-nextdc-20250901-p5mrc4

-

Hai tập đoàn báo chí lớn của Nhật Bản, Nikkei (chủ sở hữu Financial Times) và Asahi Shimbun, đã đệ đơn kiện công cụ tìm kiếm AI Perplexity tại Tokyo với cáo buộc vi phạm bản quyền.

-

Cả hai cho rằng Perplexity đã “sao chép và lưu trữ nội dung bài báo từ máy chủ của Nikkei và Asahi mà không được phép”, đồng thời bỏ qua các biện pháp kỹ thuật ngăn chặn.

-

Các nhà xuất bản khẳng định nội dung do Perplexity trả lời nhiều khi sai lệch, nhưng lại trích dẫn báo của họ, làm tổn hại nghiêm trọng đến uy tín và độ tin cậy của báo chí.

-

Nikkei và Asahi yêu cầu Perplexity phải bồi thường 2,2 tỷ yên (15 triệu USD) mỗi bên và xóa toàn bộ nội dung bị sao chép.

-

Nikkei nhấn mạnh hành động này là “ký sinh quy mô lớn” trên công sức của các nhà báo mà không trả bất kỳ khoản thù lao nào, đe dọa nền tảng của báo chí vốn dựa trên truyền tải sự thật chính xác.

-

Trước đó, Yomiuri – một tờ báo lớn khác ở Nhật – cũng đã khởi kiện Perplexity, cho thấy báo chí Nhật đang đồng loạt phản ứng trước việc AI khai thác nội dung.

-

Luật sư Kensaku Fukui cho biết luật bản quyền Nhật có một số điều khoản cho phép dùng tác phẩm có bản quyền để huấn luyện AI, nhưng cũng tồn tại giới hạn. Các vụ kiện hiện nay được coi là “test cases” để làm rõ ranh giới pháp lý.

-

Ở Mỹ và châu Âu, nhiều nhà xuất bản như Dow Jones, New York Post, BBC, New York Times và Condé Nast đã có động thái pháp lý hoặc yêu cầu Perplexity ngừng khai thác nội dung.

-

BBC đã gửi thư “cease and desist” yêu cầu Perplexity dừng dùng bài báo để huấn luyện AI, tương tự nhiều cơ quan báo chí phương Tây.

-

Dù bị kiện, Perplexity vẫn đang mở rộng quan hệ thương mại: đã ký thỏa thuận chia sẻ doanh thu với Time, Fortune và Der Spiegel, theo đó họ nhận phí khi nội dung được tham chiếu.

-

Perplexity hiện có hơn 30 triệu người dùng, phần lớn ở Mỹ, và nguồn thu chủ yếu từ gói đăng ký trả phí.

📌 Nikkei và Asahi Shimbun kiện Perplexity tại Tokyo, đòi 2,2 tỷ yên (15 triệu USD) mỗi bên vì sao chép và lưu trữ nội dung bài báo trái phép. Vụ kiện phản ánh lo ngại về việc AI làm sai lệch thông tin, làm suy yếu niềm tin báo chí. Trước đó, Yomiuri, BBC, New York Times và nhiều tờ báo lớn khác cũng đã có động thái tương tự. Dù vướng kiện, Perplexity vẫn có hơn 30 triệu người dùng và hợp tác chia sẻ doanh thu với Time, Fortune, Der Spiegel.

https://www.ft.com/content/79a88d1a-d914-4188-8792-0a20973b39a1

Japanese media groups sue AI search engine Perplexity over alleged copyright infringement

The publishers say the company illegally ‘copied and stored article content’

The Perplexity AI logo displayed on a screen

A number of media companies have taken legal action against Perplexity © REUTERS

David Keohane in Tokyo and Daniel Thomas in London

Two of Japan’s largest media groups are suing artificial intelligence search engine Perplexity over alleged copyright infringement, joining a growing list of news publishers taking legal action against AI companies using their content.

Japanese media group Nikkei, which owns the Financial Times, and the Asahi Shimbun newspaper said in statements on Tuesday that they had jointly filed a lawsuit in Tokyo.

The groups join a number of Western media companies taking legal action against Perplexity, which provides answers to questions with sources and citations, using large language models (LLMs) from platforms such as OpenAI and Anthropic.

The Japanese news providers claim Perplexity has, without permission, “copied and stored article content from the servers of Nikkei and Asahi” and ignored a “technical measure” designed to prevent this from happening.

They claim that Perplexity’s answers have given incorrect information attributed to the newspapers’ articles, which “severely damages the credibility of newspaper companies”.

Nikkei and the Asahi are asking for damages of ¥2.2bn ($15mn) each and that Perplexity delete the stored articles.

“Perplexity’s actions amount to large-scale, ongoing ‘free riding’ on article content that journalists from both companies have spent immense time and effort to research and write, while Perplexity pays no compensation,” said Nikkei in its statement.

“If left unchecked, this situation could undermine the foundation of journalism, which is committed to conveying facts accurately,” the two companies added.

Perplexity did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The lawsuits follow a similar move by another large Japanese newspaper, the Yomiuri, and signal that publishers in the country are starting to push back against AI groups, said lawyers.

“These are test cases,” said Kensaku Fukui, an expert in copyright law at law firm Kotto Dori in Tokyo.

Fukui said that while Japan’s “copyright law is in some ways permissive for AI training for existing copyrighted works . . . there are some restrictions”.

Recommended

Meta Platforms

Meta lawsuit poses first big test of AI copyright battle

Mark Zuckerberg, books, Meta logo

Rupert Murdoch’s Dow Jones and the New York Post have claimed that Perplexity is diverting customers and revenues away from news publishers by using their content to answer questions on its platform via its chatbot, rather than paying or directing readers to their websites.

The BBC this summer also demanded that Perplexity stop using its content to train its AI model in a “cease and desist” letter, similar to those sent previously by other outlets, including the New York Times and Condé Nast.

Perplexity has introduced revenue-sharing agreements with publishers including Time, Fortune and Der Spiegel, which will pay out when an answer references their work, reflecting a shift in how AI start-ups are increasingly seeking commercial partnerships and licensing agreements with publishers.

Perplexity has more than 30mn users, with the majority based in the US. Its primary source of revenue is from subscriptions.

-

AI tạo sinh đang đặt ra hai thách thức bản quyền: (1) bồi thường cho dữ liệu huấn luyện mô hình và (2) quyền sở hữu đối với sản phẩm do AI tạo ra.

-

Tại Mỹ, các tòa án và Cục Bản quyền đã khẳng định chỉ bảo vệ nội dung do con người tạo ra. Tác phẩm "A Recent Entrance to Paradise" bị từ chối bảo vệ vì không có tác giả là con người.

-

Trong trường hợp khác, truyện tranh "Zarya of the Dawn" được bảo hộ phần chữ do con người viết, còn hình ảnh AI tạo thì không được chấp nhận.

-

Trung Quốc đi ngược xu hướng này. Năm 2023, Tòa án Internet Bắc Kinh ra phán quyết công nhận quyền tác giả với hình ảnh do AI tạo ra, nếu người dùng đã đầu tư sáng tạo vào prompt và chỉnh sửa kết quả.

-

Anh và Ireland áp dụng định nghĩa “tác phẩm do máy tính tạo” được bảo hộ, nhưng đang xem xét rút lại quy định này do thiếu rõ ràng pháp lý và áp lực từ cộng đồng sáng tạo.

-

Sự khác biệt giữa các hệ thống pháp lý khiến doanh nghiệp gặp rủi ro: cùng một tác phẩm AI có thể được bảo vệ tại Bắc Kinh nhưng rơi vào phạm vi công cộng tại Boston.

-

Phần mềm là ví dụ điển hình: đoạn mã do AI viết có thể không được bảo hộ ở Mỹ, dù sản phẩm phần mềm tổng thể thì có. Điều này ảnh hưởng đến giao dịch doanh nghiệp liên quan đến quyền sở hữu trí tuệ.

-

Các hợp đồng hiện tại (với nhân viên và đối tác) thường có điều khoản chuyển nhượng bản quyền, nhưng nếu nội dung không được bảo vệ thì không thể chuyển nhượng.

-

Việc cấm hoàn toàn sử dụng AI là phi thực tế; thay vào đó, luật sư nên xây dựng hợp đồng mới, bảo vệ đầu ra AI thông qua bí mật thương mại và bảo mật thông tin.

-

Hội đồng AI Ireland đề xuất chính phủ xây dựng hình thức bảo hộ IP giới hạn cho một số tác phẩm AI, nhưng bị giới sáng tạo phản đối mạnh mẽ.

-

Trong bối cảnh luật bản quyền lỗi thời, các vụ kiện như từ Getty Images và The New York Times tập trung vào việc khai thác dữ liệu huấn luyện, nhưng quyền sở hữu tác phẩm AI vẫn chưa được tòa án xét xử rộng rãi.

📌 Bản quyền tác phẩm AI đang gây tranh cãi toàn cầu: Mỹ từ chối bảo vệ nếu không có yếu tố con người, Trung Quốc công nhận nếu có đầu tư sáng tạo vào prompt, còn châu Âu thì mập mờ. Doanh nghiệp cần nhanh chóng điều chỉnh chiến lược sở hữu trí tuệ, ưu tiên bí mật thương mại thay vì trông chờ vào luật bản quyền truyền thống.

https://www.ft.com/content/74b1841f-bf57-4934-a06a-3611d61e4319

Who owns the copyright for AI work?

-

Các nhóm công nghệ kêu gọi tòa phúc thẩm chặn vụ kiện bản quyền tập thể lớn nhất từng có, liên quan đến huấn luyện AI của Anthropic, với tới 7 triệu nguyên đơn tiềm năng, mỗi trường hợp có thể bị phạt tới 150.000 USD.

-

Anthropic cảnh báo nếu vụ kiện tiến tới xét xử trong 4 tháng tới, công ty đối mặt nguy cơ bồi thường hàng trăm tỷ USD, buộc phải dàn xếp và tạo tiền lệ nguy hiểm cho toàn ngành AI.

-

Hiệp hội Công nghệ Tiêu dùng và Hiệp hội Máy tính & Truyền thông ủng hộ kháng cáo, cho rằng quyết định chứng nhận lớp của tòa sơ thẩm đe dọa năng lực cạnh tranh toàn cầu của AI Mỹ và sẽ làm nản lòng đầu tư.

-

Các nhóm bảo vệ tác giả như Authors Alliance, EFF, ALA, ARL, Public Knowledge cũng cảnh báo việc chứng minh quyền sở hữu tác phẩm là cực kỳ phức tạp, từng khiến Google Books tốn 34,5 triệu USD lập “Books Rights Registry”.

-

Lo ngại bao gồm: tác giả đã mất, nhà xuất bản phá sản, quyền sở hữu chia nhỏ, tác phẩm “mồ côi” không xác định được chủ sở hữu, và nguy cơ phải xử lý “hàng trăm phiên tòa nhỏ” để phân định quyền.

-

Nhiều tác giả có thể không biết vụ kiện để kịp “opt-out”, gây vấn đề về công bằng và quyền tố tụng.

-

Mối quan hệ căng thẳng giữa tác giả và nhà xuất bản về AI có thể khiến một bên muốn tham gia kiện, bên kia phản đối, làm phức tạp thêm.

-

Các nhóm cảnh báo vụ kiện này có thể trở thành “đòn kết liễu” (death knell) cho việc xác định tính hợp pháp của huấn luyện AI với tác phẩm có bản quyền, khi bị ép dàn xếp thay vì giải quyết triệt để về mặt pháp lý.

📌 Anthropic đang đối mặt vụ kiện bản quyền tập thể với 7 triệu nguyên đơn tiềm năng, rủi ro bồi thường hàng trăm tỷ USD. Các nhóm công nghệ và bảo vệ tác giả cảnh báo vụ kiện có thể phá sản ngành AI, tạo tiền lệ nguy hiểm và khiến tranh cãi pháp lý về huấn luyện AI với dữ liệu bản quyền rơi vào bế tắc.

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/08/ai-industry-horrified-to-face-largest-copyright-class-action-ever-certified/

-

Các tập đoàn công nghệ lớn như Google, Amazon và Meta đang chi hàng trăm tỷ USD để mở rộng hạ tầng AI, đặc biệt là trung tâm dữ liệu và hệ thống siêu máy tính khổng lồ.

-

Riêng trong năm 2025, Google sẽ chi 85 tỷ USD cho AI và cloud (tăng 10 tỷ so với dự kiến ban đầu), trong khi Amazon chi tới 100 tỷ USD, phần lớn cũng đổ vào AI.

-

Meta dự kiến chi 64–72 tỷ USD trong năm 2025 và lên kế hoạch xây dựng mạng lưới trung tâm dữ liệu khổng lồ trên toàn nước Mỹ, hoạt động từ năm 2026.

-

Tuy nhiên, việc xây dựng trung tâm dữ liệu quy mô lớn đang gây ra áp lực lớn lên lưới điện, môi trường và nguồn tài nguyên tự nhiên, đặc biệt ở những khu vực lân cận cơ sở hạ tầng AI.

-

Trong khi đó, ngành sáng tạo đối mặt khủng hoảng. AI đang thay thế hàng loạt công việc của nghệ sĩ, chiến lược gia và nhà sáng tạo nội dung, dẫn đến sa thải và tranh chấp bản quyền.

-

CEO OpenAI Sam Altman tuyên bố: “95% công việc sáng tạo hiện nay sẽ được AI làm thay – gần như miễn phí.”

-

Hàng loạt nghệ sĩ, trong đó có Sarah Silverman và Ta-Nehisi Coates, đã kiện các công ty AI như OpenAI, Meta, Microsoft, Google vì sử dụng tác phẩm mà không xin phép, nhưng phần lớn các công ty AI đang thắng thế nhờ lập luận "sử dụng hợp lý" (fair use).

-

Adobe là công ty công nghệ hiếm hoi cố gắng cân bằng lợi ích khi giới thiệu Firefly AI – được huấn luyện từ dữ liệu có bản quyền và công khai – và công cụ Content Authenticity giúp nghệ sĩ “ký tên số” vào tác phẩm để bảo vệ quyền sở hữu.

-

Adobe tuyên bố không thu thập dữ liệu từ Internet mở vì nguy cơ vi phạm bản quyền. Họ tập trung vào sự minh bạch và khả năng xác minh nguồn gốc nội dung.

-

Theo Adobe, tương lai của sáng tạo số phải giống như “nhãn dinh dưỡng” cho nội dung – mọi người cần quyền được biết nội dung đến từ AI hay con người.

📌 Cuộc chạy đua AI của các “ông lớn” Google, Amazon và Meta đang tiêu tốn hàng trăm tỷ USD và gây ra hậu quả nghiêm trọng đến môi trường, hệ thống điện và ngành sáng tạo. Khi nghệ sĩ mất quyền kiểm soát tác phẩm, hàng loạt vụ kiện nổ ra. Trong khi đó, các công ty như Adobe chọn hướng đi minh bạch hơn, nhấn mạnh đạo đức và quyền của người sáng tạo trong thời đại AI.

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/jul/28/techscape-ai-google-meta-amazon

-

FlexOlmo là mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn mới do Allen Institute for AI (Ai2) phát triển, cho phép chủ dữ liệu rút dữ liệu khỏi mô hình ngay cả sau khi đã huấn luyện.

-

Mô hình này phá vỡ nguyên lý truyền thống rằng “dữ liệu đã dùng thì không thể gỡ”, bằng cách cho phép huấn luyện theo cách chia tách và hợp nhất các sub-model độc lập.

-

Cơ chế hoạt động dựa trên kiến trúc mixture of experts, cho phép kết hợp nhiều mô hình nhỏ, trong đó mỗi mô hình có thể được huấn luyện riêng biệt với dữ liệu riêng.

-

Người đóng góp dữ liệu sao chép một mô hình “anchor” công khai, huấn luyện với dữ liệu cá nhân, rồi gửi bản kết hợp thay vì phải chia sẻ dữ liệu thô.

-

Điều này giúp giữ quyền sở hữu dữ liệu, cho phép rút sub-model nếu có tranh chấp pháp lý hoặc không hài lòng với việc sử dụng mô hình cuối.

-

FlexOlmo không yêu cầu huấn luyện đồng bộ – việc đóng góp và huấn luyện có thể diễn ra hoàn toàn độc lập.

-

Ai2 đã thử nghiệm bằng cách xây dựng mô hình 37 tỷ tham số trên tập dữ liệu Flexmix, bao gồm sách và nội dung từ web độc quyền.

-

Mô hình này vượt trội so với từng mô hình riêng lẻ và tốt hơn 10% so với các phương pháp hợp nhất mô hình trước đó trên các benchmark phổ biến.

-

FlexOlmo còn giúp các công ty truy cập dữ liệu nhạy cảm mà không cần tiết lộ công khai, nhưng Ai2 cảnh báo vẫn có rủi ro khôi phục dữ liệu – cần đến các kỹ thuật như differential privacy.

-

Trong bối cảnh tranh cãi về quyền sở hữu dữ liệu huấn luyện AI ngày càng gay gắt, mô hình như FlexOlmo mở ra hướng đi mới cân bằng giữa tiến bộ công nghệ và quyền lợi dữ liệu.

📌 FlexOlmo mang đến một đột phá lớn trong lĩnh vực AI tạo sinh bằng cách cho phép các chủ sở hữu dữ liệu rút dữ liệu khỏi mô hình sau huấn luyện mà không cần retrain. Với 37 tỷ tham số và hiệu suất cao hơn 10% so với phương pháp cũ, mô hình này giúp cân bằng giữa phát triển AI và kiểm soát dữ liệu cá nhân, mở ra tương lai mới cho AI nguồn mở và hợp tác.

https://www.wired.com/story/flexolmo-ai-model-lets-data-owners-take-control/

A New Kind of AI Model Lets Data Owners Take Control

-

Các công ty công nghệ như Anthropic và Meta vừa giành được các chiến thắng pháp lý quan trọng trong cuộc chiến bản quyền xoay quanh việc sử dụng văn bản để huấn luyện AI.

-

Thẩm phán William Alsup so sánh hành động của Anthropic với "người đọc học viết", cho rằng việc AI đọc sách để huấn luyện không vi phạm bản quyền – dù công ty đã số hóa và hủy 7 triệu quyển sách sau khi quét nội dung từ bản giấy.

-

Thẩm phán Vince Chhabria trong vụ kiện Meta cho rằng nguyên đơn không đưa ra đủ bằng chứng về việc AI của Meta gây “loãng thị trường” (market dilution) đối với các tác phẩm gốc.

-

Tuy nhiên, vẫn còn các vụ kiện lớn đang tiếp diễn, như New York Times kiện OpenAI và Microsoft, và các hãng phim kiện Midjourney vì sử dụng nhân vật nổi tiếng như Darth Vader, gia đình Simpson mà không được phép.

-

Luật sư John Strand nhận định rằng tác động lên thị trường là yếu tố then chốt trong phân tích “fair use”, và điều đó khác biệt rõ rệt giữa sách, ảnh, video và nhạc.

-

Với ảnh và video, khả năng thắng kiện của bên giữ bản quyền cao hơn do AI có xu hướng tạo ra bản sao y hệt hình ảnh huấn luyện.

-

Một chi tiết kỳ lạ từ vụ Anthropic: họ đã mua sách thật, hủy chúng sau khi scan, tạo hình ảnh rõ ràng về “sự tiêu thụ nội dung” của AI – diễn giải vật lý của câu "train fast, break things".

-

Trong lĩnh vực nhạc, các công ty như Suno và Udio đang bị kiện vì tạo nhạc AI từ dữ liệu không cấp phép, khác với một số đối thủ đã mua bản quyền.

-

Trên mặt trận khác, WhatsApp sắp triển khai tóm tắt tin nhắn bằng AI cho người dùng – tính năng từng bị Apple thất bại khi thử nghiệm.

-

Trong y tế, DeepMind của Google công bố AlphaGenome, mô hình AI tiên tiến có thể dự đoán tác động của từng biến dị gen – mở ra tương lai cho công nghệ chỉnh sửa gen như Crispr.

-

Cũng trong tuần, Tòa án tối cao Mỹ đã ủng hộ luật kiểm soát độ tuổi tại Texas, buộc người dùng phải xác minh danh tính trước khi truy cập nội dung khiêu dâm – điều được cho là sẽ mở đường cho các bang khác siết chặt quy định truy cập nội dung nhạy cảm trực tuyến.

📌 Meta và Anthropic vừa giành các phán quyết thuận lợi về “fair use” khi huấn luyện AI bằng sách, tạo tiền lệ quan trọng trong cuộc chiến pháp lý AI. Trong khi đó, các ngành như âm nhạc và hình ảnh vẫn có nhiều cơ hội thắng kiện hơn do dễ chứng minh thiệt hại. WhatsApp chuẩn bị dùng AI tóm tắt tin nhắn, còn Google ra mắt AlphaGenome hỗ trợ phân tích gen. Cục diện AI - bản quyền ngày càng phức tạp, và luật pháp vẫn đang được viết lại.

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/jun/30/ai-techscape-copyright

-

Ngành âm nhạc đang sử dụng luật bản quyền âm thanh chặt chẽ để tấn công các công ty AI như Suno và Udio, với các cáo buộc huấn luyện mô hình trên dữ liệu vi phạm bản quyền và tạo ra sản phẩm cạnh tranh trực tiếp với bản gốc.

-

Các công ty AI như Suno cho phép người dùng tạo bài hát chỉ từ vài từ mô tả, đe dọa không phải ngôi sao như Taylor Swift, mà là những nhạc sĩ làm nhạc nền, thiền, thư giãn hoặc quảng cáo – những người bị AI "lấn sân" nghiêm trọng.

-

Suno và Udio đã thừa nhận sử dụng nhạc bản quyền trong dữ liệu huấn luyện và tuyên bố đó là "fair use", nhưng giới luật sư nhận định ngành âm nhạc có vị thế pháp lý mạnh hơn nhờ tiền lệ từ các vụ kiện sampling trái phép.

-

RIAA kiện cả ở đầu vào và đầu ra: từ hành vi sao chép trái phép khi huấn luyện đến sản phẩm AI mô phỏng tên ca sĩ nổi tiếng hoặc phong cách nhạc cụ thể.

-

Theo luật sư Grimmelman và các tiền lệ như Bridgeport Music v. Dimension Films hay Grand Upright v. Warner Bros., âm nhạc có thể được xem là "vùng cấm" với AI do bảo hộ bản ghi âm mạnh hơn hình ảnh hay văn bản.

-

Một số công ty đã chọn hướng hợp pháp: ví dụ BandLab’s SongStarter tạo track AI có cấp phép. BandLab đang đàm phán cấp phép AI trị giá hàng trăm nghìn USD trong nhiều năm, có điều khoản rõ ràng về mục đích sử dụng.

-

Giá dữ liệu âm nhạc cho huấn luyện AI dao động từ 1–5 USD/phút cho quyền không độc quyền, và 5–20 USD/phút cho quyền độc quyền. Nhãn nhạc coi đó là thị trường chính thống, không thể bỏ qua.

-

Các AI tạo nhạc như Suno cũng bị tố tạo nhạc giống đến mức vi phạm các tác phẩm hiện hữu. Một số thử nghiệm cho thấy Suno có thể "vô tình" mô phỏng gần y hệt các bản nhạc nổi tiếng.

-

Sau khi ChatGPT ra mắt, nhiều công ty AI lao vào "cướp" dữ liệu trực tuyến và chờ tòa án xử lý, thay vì xin phép. Tuy nhiên, âm nhạc không giống sách hay hình ảnh – nó có lịch sử pháp lý riêng, khả năng kiểm soát thị trường cao và tập trung vào vài hãng lớn có thể hành động tập thể.

-

Các phán quyết gần đây như vụ kiện giữa Anthropic hay Meta chưa mang lại kết luận chung, nhưng âm nhạc vẫn được xem là có khả năng thắng cao hơn, nhờ thị trường cấp phép rõ ràng và thiệt hại dễ chứng minh.

📌 Ngành âm nhạc đang dẫn đầu cuộc phản công AI bằng luật bản quyền: kiện Suno và Udio vì huấn luyện và tạo nhạc trái phép. Với lịch sử pháp lý vững chắc, hệ thống cấp phép rõ ràng và giá trị thị trường cao (1–20 USD/phút âm nhạc), các hãng nhạc đang "bóp cò" như thời Napster. AI giờ không chỉ cần thông minh – mà còn cần xin phép.

https://www.theverge.com/ai-artificial-intelligence/695290/suno-udio-ai-music-legal-copyright-riaa

-

Vào tháng 2/2024, công ty AI Anthropic đã thuê Tom Turvey, cựu giám đốc đối tác của dự án Google Books, để dẫn đầu chiến dịch quét và số hóa “tất cả sách trên thế giới”.

-

Anthropic chi hàng triệu USD để mua sách in, sau đó cắt bỏ bìa, tháo rời từng trang để quét thành file PDF có thể đọc máy, sau đó vứt bỏ bản gốc vật lý.

-

Khác với Google Books sử dụng công nghệ quét không phá hủy, Anthropic chọn phương pháp quét phá hủy nhằm tiết kiệm chi phí và thời gian trong bối cảnh cạnh tranh khốc liệt của ngành AI.

-

Theo hồ sơ tòa án, ban đầu Anthropic đã sử dụng các bản sách lậu trên mạng để huấn luyện AI, nhưng sau đó lo ngại rủi ro pháp lý nên chuyển sang phương thức mua sách vật lý.

-

Việc này dựa vào nguyên lý “first-sale doctrine” (quyền sử dụng sau bán): mua sách rồi có thể sử dụng bản đó theo ý mình, bao gồm cả việc phá hủy để số hóa.

-

Tòa án, dưới sự chủ trì của thẩm phán William Alsup, phán quyết rằng hành vi này được coi là “fair use” (sử dụng hợp lý) vì Anthropic đã mua hợp pháp sách, không phân phối lại dữ liệu mà chỉ dùng nội bộ để huấn luyện AI.

-

Thẩm phán ví hành động này như việc chuyển đổi định dạng để tiết kiệm không gian, và coi đây là hành vi mang tính “chuyển đổi”.

-

Anthropic mua sách cũ với số lượng lớn từ các nhà bán lẻ lớn, không có ghi nhận về việc phá hủy sách hiếm hay quý hiếm.

-

Quy trình số hóa của Anthropic đi ngược lại với các mô hình bảo tồn văn hóa như Internet Archive hay OpenAI-Harvard, vốn sử dụng phương pháp quét không phá hủy để bảo tồn sách cổ và tài liệu quý.

-

Trong khi Harvard đang bảo tồn các bản thảo từ thế kỷ 15 để huấn luyện AI, thì hàng triệu cuốn sách bị phá hủy đã góp phần tạo nên Claude – AI có khả năng giúp người dùng viết văn, thảo luận văn học và xử lý kiến thức.

📌 Anthropic chi hàng triệu USD mua sách in rồi tiêu hủy để huấn luyện AI Claude, bất chấp tranh cãi đạo đức. Quy trình quét phá hủy giúp tiết kiệm chi phí so với quét không phá hủy. Tòa án Mỹ xác nhận hành vi này là “fair use” nhờ mua hợp pháp và không phân phối lại. Đây là trường hợp điển hình về cơn khát dữ liệu chất lượng cao trong cuộc đua AI hiện nay.

https://arstechnica.com/ai/2025/06/anthropic-destroyed-millions-of-print-books-to-build-its-ai-models/

-

Meta vừa giành chiến thắng trong vụ kiện bản quyền AI tại tòa án liên bang San Francisco, liên quan đến việc sử dụng hàng triệu cuốn sách, bài báo học thuật và truyện tranh để huấn luyện mô hình AI Llama.

-

Thẩm phán Vince Chhabria phán quyết rằng việc Meta sử dụng các tài liệu này thuộc phạm trù "sử dụng hợp lý" (fair use) theo luật bản quyền.

-

Vụ kiện do khoảng 12 tác giả nổi tiếng khởi kiện, bao gồm Ta-Nehisi Coates và Richard Kadrey. Họ cáo buộc Meta sử dụng thư viện trực tuyến LibGen - nơi lưu trữ nội dung vi phạm bản quyền - để huấn luyện AI mà không xin phép.

-

Thẩm phán nhấn mạnh rằng phán quyết này không có nghĩa là hành vi của Meta hoàn toàn hợp pháp, mà chỉ phản ánh việc phía nguyên đơn "đưa ra lập luận sai" và "không xây dựng được hồ sơ đầy đủ để bảo vệ quan điểm của mình".

-

Đây là chiến thắng thứ hai liên tiếp trong tuần của các công ty công nghệ AI, sau khi một thẩm phán khác xử thắng cho Anthropic. Anthropic bị cáo buộc sử dụng sách giấy mua hợp pháp rồi cắt nhỏ và quét để huấn luyện mô hình Claude. Tòa phán quyết đây là "sử dụng hợp lý", nhưng vẫn yêu cầu xét xử riêng đối với cáo buộc tải lậu hàng triệu sách điện tử.

-

Thẩm phán cũng chỉ ra rằng, một lập luận tiềm năng có thể thắng trong vụ Meta là "làm loãng thị trường", tức là thiệt hại kinh tế đối với chủ bản quyền do AI tạo ra vô hạn các sản phẩm như hình ảnh, bài hát, bài báo hoặc sách.

-

Ông cảnh báo rằng AI tạo sinh có thể "làm suy yếu nghiêm trọng động lực sáng tạo truyền thống của con người" khi người dùng chỉ cần một phần nhỏ thời gian và công sức để tạo ra sản phẩm tương tự.

-

Hiện Meta và đại diện pháp lý của các tác giả chưa đưa ra bình luận chính thức về vụ việc.

📌 Meta vừa giành thắng lợi lớn trong vụ kiện bản quyền AI, khi tòa án San Francisco phán quyết việc sử dụng sách huấn luyện AI thuộc phạm trù "sử dụng hợp lý". Thẩm phán cho biết nguyên đơn thất bại do lập luận yếu. Vụ kiện liên quan đến kho dữ liệu LibGen và đặt ra nguy cơ AI làm suy yếu thị trường sáng tạo truyền thống. Đây cũng là chiến thắng thứ hai trong tuần của ngành AI, sau chiến thắng của Anthropic.

https://www.ft.com/content/6f28e62a-d97d-49a6-ac3b-6b14d532876d

#FT

Meta wins artificial intelligence copyright case in blow to authors

-

Ca sĩ – nhạc sĩ Elton John đã gay gắt chỉ trích chính phủ Anh khi gọi họ là “absolute losers” (lũ thất bại) do kế hoạch thay đổi luật bản quyền cho phép các công ty AI sử dụng nội dung có bản quyền mà không cần xin phép.

-

Trong chương trình “Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg” trên BBC One, ông nói việc này là “một hành vi phạm tội” và khẳng định sẽ kiện chính phủ nếu kế hoạch không thay đổi.

-

Elton John cho rằng kế hoạch này sẽ “cướp đi di sản và thu nhập của giới trẻ” và cảm thấy “bị phản bội nghiêm trọng”.

-

Ông gọi Bộ trưởng Công nghệ Peter Kyle là “kẻ ngốc” và chỉ trích sự gần gũi bất thường giữa ông Kyle và các tập đoàn công nghệ lớn như Google, Amazon, Apple và Meta – vốn tăng đột biến sau khi Đảng Lao động thắng cử tháng 7/2024.

-

Trước cuộc bỏ phiếu tại Thượng viện, Elton John ủng hộ đề xuất của nữ nghị sĩ Beeban Kidron, yêu cầu các công ty AI công khai khi sử dụng nội dung có bản quyền để các nghệ sĩ có thể thương lượng cấp phép.

-

Một sửa đổi tương tự trước đó đã được Thượng viện thông qua với tỷ lệ hơn 2:1 nhưng sau đó bị chính phủ loại bỏ khi trình lên Hạ viện, làm dấy lên xung đột lập pháp nghiêm trọng.

-

Chính phủ Anh hiện đang tham vấn các phương án liên quan đến đào tạo AI trên dữ liệu có bản quyền, trong đó có:

-

Giữ nguyên luật hiện hành;

-

Yêu cầu công ty AI phải xin giấy phép sử dụng;

-

Cho phép sử dụng mà không cần xin phép, trừ khi chủ sở hữu từ chối;

-

Hoặc hoàn toàn cho phép mà không có cơ chế từ chối.

-

-

Dù một nguồn tin thân cận cho biết phương án “cho phép mặc định” không còn là lựa chọn ưu tiên, nhưng nó vẫn được giữ lại trong tham vấn.

-

Người phát ngôn chính phủ cho biết sẽ không thay đổi luật bản quyền nếu không đảm bảo quyền lợi cho người sáng tạo, đồng thời cam kết thực hiện đánh giá tác động kinh tế toàn diện.

📌 Elton John phản ứng gay gắt với kế hoạch cho phép AI sử dụng nội dung có bản quyền mà không xin phép, gọi đây là hành vi “phạm tội”. Ông đe dọa kiện nếu chính phủ không thay đổi chính sách. Trong khi đó, các lựa chọn đang được chính phủ Anh tham vấn bao gồm cả việc bỏ cơ chế từ chối, gây lo ngại lớn cho giới sáng tạo.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2025/may/18/elton-john-says-uk-government-being-absolute-losers-over-ai-copyright-plans

-

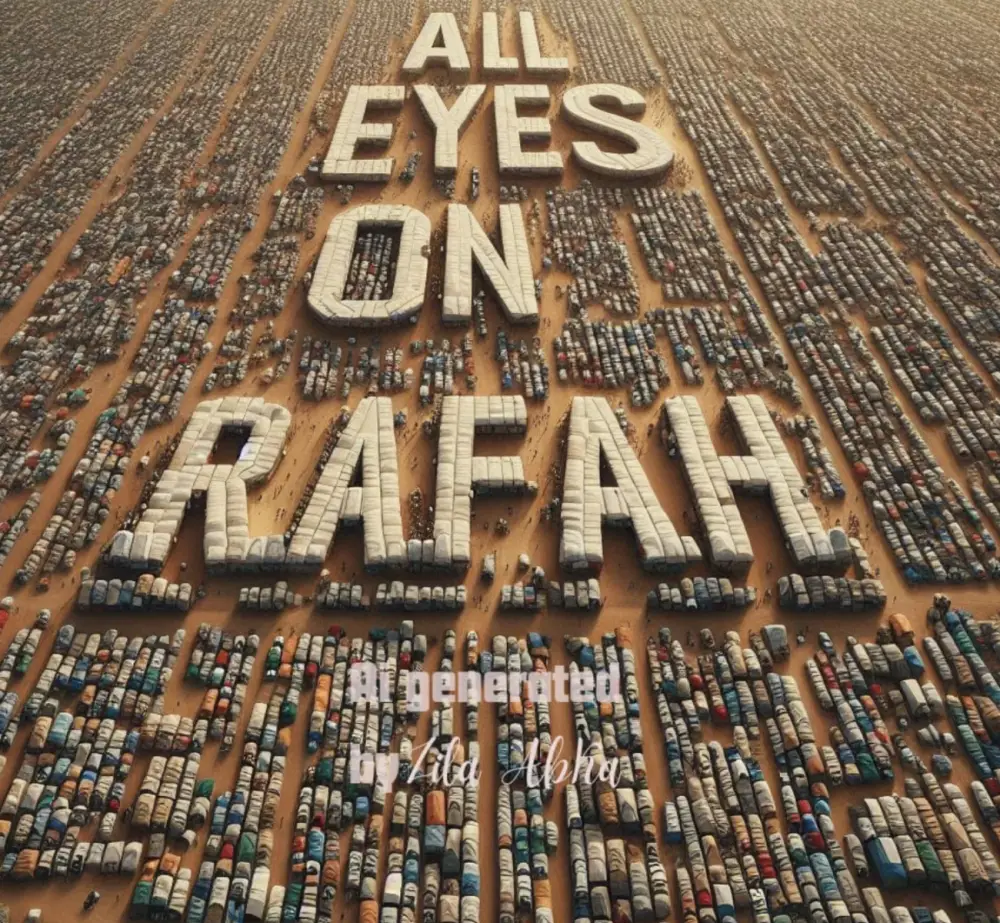

OpenAI vừa ra mắt bản nâng cấp mới cho ChatGPT với khả năng tạo ảnh theo phong cách các studio nổi tiếng, dẫn đến làn sóng hình ảnh “Ghibli hóa” tràn lan trên mạng, thu hút 1 triệu người dùng chỉ trong 1 giờ.

-

Phong cách của Studio Ghibli – nổi tiếng với các bộ phim như Spirited Away và Princess Mononoke – trở thành xu hướng mạnh nhất, được dùng trong ảnh gia đình, các sự kiện lịch sử như 9/11. Sam Altman, CEO của OpenAI, còn đổi avatar thành phiên bản “Ghibli hóa” của chính mình.

-

Dù người dùng xem đây là trào lưu tự phát, Altman thừa nhận công ty đã cân nhắc kỹ các ví dụ minh họa khi ra mắt tính năng. OpenAI chủ động thúc đẩy xu hướng, có thể ví như một chiến dịch tiếp thị trá hình.

-

Vấn đề pháp lý chính nằm ở việc phong cách hình ảnh không được bảo vệ bản quyền, nhưng luật “right of publicity” và “false endorsement” (giả mạo chứng thực) có thể áp dụng. Ví dụ, ca sĩ Bette Midler thắng kiện với 400.000 USD khi bị bắt chước phong cách hát.

-

OpenAI từng gặp rủi ro tương tự khi sử dụng giọng nói giống Scarlett Johansson, dù đã xin lỗi và gỡ bỏ.

-

Giới nghệ sĩ lo ngại AI tạo sinh phá vỡ thị trường nghệ thuật. Phong cách cá nhân như của Miyazaki mất giá trị khi có thể bị tái tạo hàng loạt bởi AI mà không cần nỗ lực sáng tạo thực sự.

-

Các vụ kiện đang diễn ra với Midjourney vì các lý do tương tự, có thể tạo tiền lệ pháp lý cho trường hợp của OpenAI.

-

Nghệ sĩ Greg Rutkowski từng chia sẻ rằng ảnh AI giả danh ông đang làm lu mờ tác phẩm thật. Theo cựu cố vấn pháp lý của Adobe, luật hiện hành không đủ để bảo vệ phong cách sáng tạo cá nhân.

📌 ChatGPT đang tạo làn sóng tranh cãi khi sử dụng phong cách Studio Ghibli mà không xin phép, gây nguy cơ kiện tụng vì vi phạm “right of publicity” và “false endorsement”. Với 1 triệu người dùng trong 1 giờ, trào lưu này không chỉ đe dọa sinh kế nghệ sĩ mà còn khiến xã hội phải suy xét lại ranh giới đạo đức và pháp lý của AI tạo sinh.

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2025/05/openai-studio-ghibli-images/682791/

-

Văn phòng bản quyền Mỹ đã công nhận bảo hộ cho hơn 1.000 tác phẩm có yếu tố AI tạo sinh tham gia vào quá trình sáng tạo.

-

Quy trình xét duyệt phân biệt rõ giữa việc dùng AI làm công cụ hỗ trợ sáng tạo (có thể bảo hộ) và AI thay thế hoàn toàn sáng tạo của con người (không được bảo hộ).

-

Luật sư Jalyce Mangum giải thích: AI chỉ có vai trò hợp lệ khi giúp con người thể hiện ý tưởng sáng tạo, không phải nguồn gốc các lựa chọn sáng tạo chính.

-

Ví dụ điển hình: ca sĩ Randy Travis sử dụng AI để tái tạo giọng hát cho bản thu âm "Where That Came From", giúp ông sáng tác dù đã mất khả năng nói sau đột quỵ – tác phẩm này được bảo hộ bản quyền.

-

Ở Hàn Quốc, một bộ phim do AI tạo ra hoàn toàn vẫn được bảo hộ bản quyền nhờ sự sáng tạo ở khâu lựa chọn, phối hợp và sắp xếp nội dung AI của con người.

-

Năm 2024, Metro Boomin ra mắt ca khúc sử dụng toàn bộ mẫu nhạc từ công cụ Udio AI, thu hút 3,4 triệu lượt nghe trên SoundCloud. Tuy nhiên, Udio lại đối mặt với vụ kiện bản quyền từ hiệp hội RIAA.

-

Tranh cãi bản quyền AI ngày càng kịch liệt: Paul McCartney cảnh báo AI có thể khiến nghệ sĩ mất quyền lợi; nhiều nhạc sĩ, nhiếp ảnh gia kiện các công ty AI lớn vì sử dụng tác phẩm của họ để huấn luyện mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn.

-

Ở châu Âu, Đạo luật AI vừa được thông qua, cấm các công cụ AI rủi ro cao, đồng thời siết chặt yêu cầu tuân thủ bản quyền.

-

Luật bảo hộ bản quyền AI mới chỉ định hướng cho nghệ sĩ sáng tạo công nghệ, nhưng chưa làm dịu các chỉ trích mạnh mẽ về rủi ro AI gây ra cho ngành sáng tạo toàn cầu.

📌 Hơn 1.000 tác phẩm có yếu tố AI đã được Mỹ công nhận bảo hộ bản quyền nếu AI chỉ đóng vai trò hỗ trợ sáng tạo. Dù luật bảo hộ giúp mở đường cho nghệ thuật AI, tranh cãi và kiện tụng vẫn bùng nổ liên quan tới ranh giới sáng tạo giữa người và máy.

https://www.pcmag.com/news/one-thousand-ai-enhanced-works-now-protected-by-us-copyright-law

-

AI tạo sinh đang làm thay đổi sâu rộng ngành webtoon tại Hàn Quốc, điển hình là việc huyền thoại truyện tranh Lee Hyun-se hợp tác AI để "bất tử hóa" các nhân vật kinh điển của mình như Kkachi, Umji, Ma Dong-tak.

-

Lee Hyun-se phát triển mô hình AI cá nhân bằng cách tinh chỉnh Stable Diffusion trên dữ liệu 5.000 tập truyện do mình sáng tác trong suốt 46 năm cùng Jaedam Media, giúp tạo ra tranh mang phong cách đặc trưng của ông.

-

Chuỗi truyện đầu tiên dùng AI hỗ trợ của Lee là bản làm lại "Karon’s Dawn", hiện đại hóa nhân vật trong bối cảnh Seoul ngày nay, với sự tham gia sáng tác của sinh viên Đại học Sejong.

-

Quy trình sáng tác gồm: AI tạo hình ảnh dựa trên mô tả, sinh viên biên tập lại biểu cảm, động tác và Lee định hình tổng thể, bổ sung chi tiết cảm xúc mà AI chưa làm được.

-

Lee đặt mục tiêu xây dựng "Lee Hyun-se simulation agent"—một agent AI có tính chủ thể, mô phỏng tư duy sáng tạo bằng cách huấn luyện trên các tiểu luận, phỏng vấn, và bản thảo truyện của ông.

-

AI giúp rút ngắn thời gian sản xuất truyện tranh từ 6 tháng xuống chỉ còn 2 tuần, hỗ trợ nghệ sĩ độc lập, loại bỏ nhu cầu thuê ê-kíp lớn như trước.

-

Startup Onoma AI phát triển TooToon—phần mềm tạo truyện tranh bằng AI, cho phép người dùng soạn tóm tắt, tạo nhân vật, và hình ảnh chỉ từ mô tả và phác thảo đơn giản.

-

Quá trình này gây tranh cãi mạnh mẽ về bản quyền; nhiều nghệ sĩ và độc giả phát động phong trào tẩy chay truyện tranh AI, đặc biệt khi các nền tảng như Naver Webtoon yêu cầu nghệ sĩ đồng ý cho AI sử dụng tác phẩm để huấn luyện.

-

Ủy ban Bản quyền Hàn Quốc ban hành hướng dẫn: AI chỉ được sử dụng dữ liệu có sự đồng ý chủ sở hữu, quy định rõ phạm vi, mục đích và vấn đề đền bù, song chưa có khung pháp lý rõ ràng.

-

Trong khi nghệ sĩ lão làng như Lee xem AI là công cụ mở rộng di sản, phần lớn nghệ sĩ trẻ lo sợ mất quyền làm chủ sáng tạo, mất luôn phần "linh hồn" của tác phẩm vào tay thuật toán.

-

Một số nghệ sĩ chuyên về cốt truyện như Bae Jin-soo lại coi AI là trợ lý hữu ích, giúp tự động hóa khâu vẽ để tập trung vào kịch bản, dù vẫn lo ngại việc này sẽ bào mòn cá tính nghệ thuật.

-

Trường Đại học Sejong đào tạo sinh viên thành "creative coder", tích hợp AI vào quá trình sáng tác truyện, mở ra tiềm năng sáng tạo thể loại, nhân vật đa dạng hơn nhờ tiết kiệm được thời gian.

-

Tổng thể, AI tạo sinh vừa mở ra kỷ nguyên sáng tạo mới, vừa đặt ra câu hỏi lớn về quyền tác giả, bản sắc nghệ sĩ và "linh hồn" của nghệ thuật.

📌 AI tạo sinh đang cách mạng hóa ngành webtoon Hàn Quốc: giúp rút ngắn thời gian sản xuất xuống 2 tuần, hỗ trợ cả nghệ sĩ lão làng lẫn độc lập, nhưng cũng châm ngòi lo ngại bản quyền, khủng hoảng bản sắc, khiến nghệ sĩ trẻ phản đối mạnh mẽ và chưa có giải pháp pháp lý rõ ràng.

https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/04/22/1114874/generative-ai-south-korea-webcomics/

#MIT

AI tạo sinh đang tái định hình ngành truyện tranh web của Hàn Quốc

Một số họa sĩ như Lee Hyun-se huyền thoại coi AI là con đường đến sự bất tử; những người khác lại băn khoăn liệu nó có phải mối đe dọa cho sự sáng tạo của họ.

Tác giả: Michelle Kim

22 tháng 4 năm 2025

"Tarot: A Tale of Seven Pages" là một series truyện tranh web do AI tạo ra bởi startup Onoma AI của Hàn Quốc.

"Trí óc tôi vẫn còn minh mẫn và tay tôi vẫn hoạt động tốt, nên tôi không quan tâm đến việc nhận trợ giúp từ AI để vẽ hay viết truyện," Lee Hyun-se, họa sĩ truyện tranh huyền thoại của Hàn Quốc nổi tiếng nhất với series manhwa đình đám A Daunting Team năm 1983 về hành trình trưởng thành của các cầu thủ bóng chày anh hùng dân dã, nói. "Tuy nhiên, tôi đã bắt tay với AI để bất tử hóa các nhân vật Kkachi, Umji và Ma Dong-tak của mình."

Bằng việc đón nhận AI generative, Lee đang mở ra biên giới sáng tạo mới trong ngành truyện tranh web của Hàn Quốc. Kể từ khi các tạp chí truyện tranh phai nhạt vào đầu thế kỷ này, truyện tranh web—những truyện tranh được đăng theo kỳ đọc từ trên xuống dưới trên các nền tảng số—đã phát triển từ văn hóa phụ thành cường quốc giải trí toàn cầu, thu hút hàng trăm triệu độc giả trên khắp thế giới. Lee từ lâu đã đi đầu trong lĩnh vực này, vượt qua các giới hạn của nghề.

Lee lấy cảm hứng cho các anh hùng bóng chày nổi loạn của mình từ Sammi Superstars, một trong những đội bóng chày chuyên nghiệp đầu tiên của Hàn Quốc, với hành trình kiên trì đã thu hút một đất nước đang bị kìm nén bởi chế độ độc tài quân sự. Series này đã có một lượng fan cuồng nhiệt trong số các độc giả tìm kiếm lối thoát sáng tạo khỏi sự đàn áp chính trị, họ bị mê hoặc bởi nét cọ táo bạo và bố cục điện ảnh của ông - thách thức các quy ước thông thường của truyện tranh.

Kkachi, nhân vật chính nổi loạn trong A Daunting Team, là một bản ngã của chính Lee. Một kẻ bị ruồng bỏ can đảm với mái tóc dựng đứng không thuần phục, anh là nhân vật được yêu thích nhất, người thách thức thế giới bằng đam mê không ngừng và lương tâm dũng cảm. Anh đã xuất hiện lại xuyên suốt các tác phẩm tiêu biểu của Lee, mỗi lần được vẽ với một lớp cảm xúc mới—một chiến binh siêu nhiên cứu Trái đất khỏi cuộc tấn công của người ngoài hành tinh trong Armageddon và một cảnh sát bất chính chiến đấu với tổ chức tội phạm hùng mạnh trong Karon's Dawn. Qua nhiều thập kỷ, Kkachi đã trở thành biểu tượng văn hóa ở Hàn Quốc.

Nhưng Lee lo lắng về tương lai của Kkachi. "Ở Hàn Quốc, khi một tác giả qua đời, các nhân vật của anh ta cũng bị chôn theo cùng mộ," ông nói, so sánh với các nhân vật truyện tranh Mỹ bền vững như Superman và Spider-Man. Lee khao khát sự bất tử nghệ thuật. Ông muốn các nhân vật của mình sống mãi không chỉ trong ký ức của độc giả mà còn trên các nền tảng truyện tranh web. "Ngay cả sau khi tôi chết, tôi muốn thế giới quan và các nhân vật của tôi tiếp tục giao tiếp và cộng hưởng với con người của kỷ nguyên mới," ông nói. "Đó là loại bất tử mà tôi mong muốn."

Lee tin rằng AI có thể giúp ông hiện thực hóa tầm nhìn này. Hợp tác với Jaedam Media, một công ty sản xuất truyện tranh web tại Seoul, ông đã phát triển "mô hình AI Lee Hyun-se" bằng cách tinh chỉnh trình tạo nghệ thuật AI mã nguồn mở Stable Diffusion, được tạo ra bởi startup Stability AI có trụ sở tại Anh. Sử dụng bộ dữ liệu 5.000 tập truyện mà ông đã xuất bản trong 46 năm, mô hình kết quả tạo ra truyện tranh theo phong cách đặc trưng của ông.

Năm nay, Lee chuẩn bị xuất bản truyện tranh web đầu tiên được hỗ trợ bởi AI, một phiên bản làm lại của manhwa Karon's Dawn năm 1994. Các nhà văn tại Jaedam Media đang chuyển thể câu chuyện thành một bộ phim tội phạm hiện đại với Kkachi đóng vai cảnh sát ở Seoul ngày nay và Umji - người yêu của anh - là một công tố viên táo bạo. Sinh viên tại Đại học Sejong, nơi Lee dạy truyện tranh, đang tạo tác phẩm nghệ thuật bằng mô hình AI của ông.

Quá trình sáng tạo diễn ra qua nhiều giai đoạn. Đầu tiên, mô hình AI của Lee tạo ra minh họa dựa trên lời nhắc văn bản và hình ảnh tham khảo, như mô hình giải phẫu 3D và bản phác thảo vẽ tay cung cấp gợi ý cho các chuyển động và cử chỉ khác nhau. Học sinh của Lee sau đó sẽ tuyển chọn và chỉnh sửa các minh họa, điều chỉnh tư thế của nhân vật, tùy chỉnh biểu cảm khuôn mặt và tích hợp chúng vào các bố cục hoạt hình mà AI không thể thiết kế. Sau nhiều vòng tinh chỉnh và tái tạo, Lee bước vào để điều phối sản phẩm cuối cùng, thêm vào dấu ấn nghệ thuật đặc trưng của mình.

Các công ty AI hình dung rằng nghệ sĩ có thể tự động hóa công việc vẽ nặng nhọc và tập trung năng lượng sáng tạo vào kể chuyện và chỉ đạo nghệ thuật.

"Dưới sự chỉ đạo của tôi, một nhân vật có thể nhìn chằm chằm với ánh mắt buồn ngay cả khi họ tức giận hoặc ánh mắt hung dữ khi họ hạnh phúc," ông nói. "Đó là biểu hiện lật ngược, một sắc thái mà AI khó nắm bắt. Những chi tiết tinh tế đó tôi cần tự mình chỉ đạo."

Cuối cùng, Lee muốn xây dựng một hệ thống AI thể hiện cách tiếp cận tỉ mỉ của ông với biểu cảm con người. Tầm nhìn lớn của dự án AI thử nghiệm của ông là tạo ra một "tác nhân mô phỏng Lee Hyun-se"—một thế hệ tiên tiến của mô hình AI của ông, sao chép tâm trí sáng tạo của ông. Mô hình sẽ được đào tạo trên kho lưu trữ số các bài tiểu luận, phỏng vấn và văn bản từ truyện tranh của Lee—chủ đề của một triển lãm tại Thư viện Quốc gia Hàn Quốc năm ngoái—để mã hóa triết lý, tính cách và giá trị của ông. "AI sẽ mất nhiều thời gian để học các thế giới quan phong phú của tôi vì tôi đã xuất bản rất nhiều tác phẩm," ông nói.

Bản sao số của Lee sẽ tạo ra truyện tranh mới với trực giác nghệ thuật của ông, nhận thức môi trường xung quanh và đưa ra lựa chọn sáng tạo như ông sẽ làm—có thể thậm chí xuất bản một series trong tương lai xa với Kkachi đóng vai nhân vật hậu nhân loại. "50 năm nữa, Lee Hyun-se sẽ tạo ra những loại truyện tranh nào nếu ông ấy nhìn thấy thế giới lúc đó?" Lee hỏi. "Câu hỏi này làm tôi say mê."

Hành trình tìm kiếm di sản nghệ thuật lâu dài của Lee là một phần của cuộc tiến hóa sáng tạo rộng lớn hơn được thúc đẩy bởi công nghệ. Trong nhiều thập kỷ kể từ khi xuất hiện, truyện tranh web đã biến đổi nghệ thuật kể chuyện, cung cấp một không gian số vô tận tích hợp âm nhạc, hoạt hình và hình ảnh tương tác với hiệu ứng từ các công cụ mới như chương trình tô màu tự động. Việc bổ sung AI đang thúc đẩy làn sóng đổi mới tiếp theo. Nhưng ngay cả khi nó mở khóa các khả năng sáng tạo mới, nó cũng đang gây lo ngại về quyền tự chủ nghệ thuật và quyền tác giả.

Năm ngoái, startup Onoma AI của Hàn Quốc, đặt tên theo từ Hy Lạp "onoma" có nghĩa là "tên" (một tín hiệu về tham vọng định nghĩa lại cách kể chuyện sáng tạo), đã ra mắt trình tạo truyện tranh web được hỗ trợ bởi AI có tên TooToon. Phần mềm cho phép người dùng tạo tóm tắt, nhân vật và storyboard bằng lời nhắc văn bản đơn giản và chuyển đổi bản phác thảo thô thành minh họa hoàn thiện phản ánh phong cách nghệ thuật cá nhân của họ. TooToon tuyên bố hợp lý hóa quá trình sáng tạo tốn nhiều công sức bằng cách giảm thời gian sản xuất từ phát triển ý tưởng đến nghệ thuật đường nét từ 6 tháng xuống chỉ còn 2 tuần.

Các công ty như Onoma AI ủng hộ ý tưởng rằng AI có thể giúp bất kỳ ai trở thành nghệ sĩ—ngay cả khi bạn không thể vẽ hoặc không đủ khả năng thuê một đội ngũ trợ lý để theo kịp yêu cầu sản xuất điên cuồng của ngành. Trong tầm nhìn của họ, các nghệ sĩ sẽ nổi lên như đạo diễn của studio solo được hỗ trợ bởi AI của riêng họ, tự động hóa công việc vẽ nặng nhọc và tập trung năng lượng sáng tạo vào kể chuyện và chỉ đạo nghệ thuật. Họ nói rằng đột phá năng suất sẽ giúp nghệ sĩ sáng tạo nhiều ý tưởng thử nghiệm hơn, đảm nhận các dự án quy mô lớn và phá vỡ thế độc quyền của các studio thống trị thị trường.

"AI sẽ mở rộng hệ sinh thái truyện tranh web," Song Min, người sáng lập và CEO của Onoma AI nói. Song mô tả ngành công nghiệp ở Hàn Quốc như một "kim tự tháp"—các nền tảng hùng mạnh như Naver Webtoon và Kakao Webtoon ở đỉnh, tiếp theo là các studio lớn, nơi các nghệ sĩ hợp tác để sản xuất hàng loạt truyện tranh web. "Phần còn lại của các nghệ sĩ, những người ngoài hệ thống studio, không thể sáng tạo một mình," ông giải thích. "AI sẽ trao quyền cho nhiều nghệ sĩ hơn nổi lên như nghệ sĩ độc lập."

Năm ngoái, Onoma AI đã hợp tác với một nhóm nghệ sĩ truyện tranh web trẻ để tạo ra Tarot: A Tale of Seven Pages, một truyện trinh thám bí ẩn làm sáng tỏ số phận xoắn xuýt của những người xa lạ bị nguyền rủa bởi một ván bài tarot. Thông qua những hợp tác này, Song sử dụng phản hồi của các nghệ sĩ để cải thiện TooToon. Tuy nhiên, ngay cả với tư cách là người ủng hộ nghệ thuật do AI tạo ra, ông cũng đặt câu hỏi liệu "AI hoàn hảo có phải là điều tốt không." Giống như các kỹ sư cần tiếp tục viết code để mài giũa kỹ năng, ông tự hỏi liệu AI có nên để lại chỗ cho nghệ sĩ tiếp tục vẽ để nuôi dưỡng nghề nghiệp của họ không.

"AI là một sức mạnh không thể tránh khỏi, nhưng hiện tại, các rào cản lớn nằm ở nhận thức của nghệ sĩ và bản quyền," ông nói.

Onoma AI đã xây dựng Illustrious, mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn cung cấp năng lượng cho TooToon, bằng cách tinh chỉnh Stable Diffusion trên bộ dữ liệu Danbooru2023, một ngân hàng hình ảnh công cộng các minh họa theo phong cách anime. Nhưng Stable Diffusion, cùng với các trình tạo hình ảnh phổ biến khác được xây dựng trên mô hình này, đã bị chỉ trích vì thu thập hình ảnh bừa bãi từ internet, gây ra một loạt vụ kiện về vi phạm bản quyền. Đến lượt mình, các trình tạo truyện tranh web đang đối mặt với phản ứng dữ dội từ các nghệ sĩ lo sợ rằng các chương trình đang được đào tạo trên nghệ thuật của họ mà không có sự đồng ý.

"Bạn có thể sáng tạo mà không có linh hồn không? Ai biết được?"

Khi các công ty che giấu dữ liệu đào tạo của họ, các nghệ sĩ và độc giả đã phát động một chiến dịch số để tẩy chay truyện tranh web do AI tạo ra. Vào tháng 5 năm 2023, độc giả đã ném bom The Knight King Returns with the Gods trên Naver Webtoon với điểm đánh giá cực thấp sau khi phát hiện AI đã được sử dụng để cải thiện các phần của tác phẩm nghệ thuật. Tháng sau, các nghệ sĩ tràn ngập nền tảng với các bài đăng ẩn danh phản đối "truyện tranh web AI được tạo ra từ trộm cắp", chỉ trích gay gắt chính sách hợp đồng của Naver yêu cầu các nghệ sĩ xuất bản trên nền tảng phải đồng ý cho phép tác phẩm của họ được sử dụng làm dữ liệu đào tạo AI.

Để giải quyết bế tắc, Ủy ban Bản quyền Hàn Quốc đã ban hành một bộ hướng dẫn vào tháng 12 năm 2023, kêu gọi các nhà phát triển AI xin phép chủ sở hữu bản quyền trước khi sử dụng tác phẩm của họ làm dữ liệu đào tạo; nêu rõ mục đích, phạm vi và thời gian sử dụng; và cung cấp khoản bồi thường công bằng. Một năm sau, giữa những lời kêu gọi ngày càng tăng từ các công ty AI về việc tiếp cận nhiều dữ liệu hơn, chính phủ Hàn Quốc đã đề xuất tạo ra một ngoại lệ cho luật bản quyền cho phép các mô hình AI được đào tạo trên các tác phẩm có bản quyền theo học thuyết sử dụng hợp lý. Nhưng chưa có luật hoặc quy định nào thiết lập khung pháp lý rõ ràng, khiến các nghệ sĩ trong tình trạng bấp bênh.

Trong khi các nghệ sĩ kỳ cựu như Lee đón nhận công nghệ này như một công cụ để mở rộng di sản của họ, hết lòng cấp phép tài sản trí tuệ của họ cho AI, các nghệ sĩ trẻ hơn lại coi nó là mối đe dọa. Họ lo sợ rằng AI sẽ đánh cắp tác phẩm nghệ thuật của họ và quan trọng hơn, danh tính của họ với tư cách là nghệ sĩ.

"Vẽ là phần khó nhất và thú vị nhất của việc làm truyện tranh," Park So-won, một nghệ sĩ truyện tranh web trẻ tại Seoul, nói. Park lớn lên với ước mơ trở thành họa sĩ truyện tranh, xem mẹ cô, một nhà làm phim hoạt hình, tạo dựng các nhân vật. Sau nhiều năm cân bằng các công việc làm trợ lý nghệ sĩ tại một studio truyện tranh web, bị gián đoạn bởi một khoảng nghỉ sáng tạo ngắn, cô đã có bước đột phá trên nền tảng Lezhin Comics với Legs That Won't Walk, một tiểu thuyết noir lãng mạn đồng tính về một võ sĩ yêu một tay cho vay nặng lãi đang truy đuổi anh vì nợ của người cha nghiện rượu.

Là một nghệ sĩ độc lập, Park liên tục làm việc. Cô xuất bản một tập mới mỗi 10 ngày, thường xuyên thức trắng đêm để tạo ra tới 80 cảnh vẽ, ngay cả khi có sự giúp đỡ của trợ lý xử lý nghệ thuật nền và tô màu. Thỉnh thoảng cô thấy mình trong trạng thái dòng chảy, làm việc 30 giờ liên tục không nghỉ.

Tuy nhiên, Park không thể tưởng tượng việc giao phác vẽ của mình, thứ cô coi là trái tim của truyện tranh, cho AI. "Yếu tố cốt lõi của một bộ truyện tranh, dù câu chuyện quan trọng đến đâu, là hình vẽ. Nếu câu chuyện được viết bằng lời, mọi người đã không đọc nó, phải không? Câu chuyện chỉ là một ý nghĩ—việc thực hiện là hình vẽ," cô nói. "Ngữ pháp của truyện tranh là hình vẽ." Giao hình vẽ của mình đồng nghĩa với việc từ bỏ quyền tự chủ nghệ thuật.

Park nghĩ nghệ thuật thuật toán thiếu linh hồn—như "những vật thể tồn tại trong khoảng không"—và không lo lắng về việc AI có thể vẽ tốt hơn cô không. Các bản vẽ của cô đã phát triển theo thời gian, được định hình bởi quan điểm thay đổi của cô về thế giới và phá vỡ giới hạn sáng tạo mới theo thời gian—một sự tiến bộ nghệ thuật mà cô nghĩ một thuật toán được đào tạo để bắt chước các tác phẩm hiện có không bao giờ có thể thực hiện. "Tôi sẽ tiếp tục mở ra lãnh thổ mới với tư cách là một nghệ sĩ, trong khi AI sẽ giữ nguyên," cô nói.

Với Park, nghệ thuật là sự đam mê tột cùng: "Tôi đã đi xa đến mức này vì tôi yêu thích vẽ. Nếu AI lấy đi điều yêu thích nhất của tôi trên đời, tôi sẽ làm gì?"

Nhưng các nghệ sĩ truyện tranh khác, những người có thế mạnh trong kể chuyện, lại chào đón sự đổi mới này. Bae Jin-soo từng là một nhà biên kịch đầy tham vọng trước khi ra mắt với tư cách nghệ sĩ trên trang truyện tranh nghiệp dư của Naver Webtoon năm 2010. Để biến kịch bản của mình thành truyện tranh, Bae tự học vẽ bằng cách chụp ảnh các bố cục khác nhau và tracing chúng lên giấy. "Tôi không thể vẽ, vì vậy tôi sẽ đặt cược vào khả năng viết của mình," anh nghĩ.

Sau khi series đầu tay Friday: Forbidden Tales thành công, Bae nổi tiếng với ba phần series Money Game, Pie Game và Funny Game—những truyện trinh thám tâm lý thông minh chứa đầy những nút thắt cốt truyện và câu chuyện dí dỏm, kích thích tư duy về một nhóm thí sinh chơi các trò chơi kỳ quặc để giành giải thưởng tiền mặt. Chúng thậm chí còn truyền cảm hứng cho một bộ phim chuyển thể nổi tiếng trên Netflix, The 8 Show.

"Tôi vẫn còn rất nhiều câu chuyện muốn kể," Bae nói. Một nhà văn sung mãn, anh giữ một danh sách các ý tưởng mới trong một cuốn sổ tay bỏ túi, các cốt truyện đa thể loại trải dài từ kinh dị, chính trị đến hài đen. Nhưng với tâm trí luôn chạy đua trước tay, việc thổi hồn vào tất cả các ý tưởng của mình sẽ đòi hỏi phải thuê một studio để thực hiện các minh họa. Đối với Bae, một trình tạo truyện tranh web được hỗ trợ bởi AI có thể là một bước đột phá. "Nếu AI có thể xử lý tác phẩm nghệ thuật của tôi, tôi sẽ tạo ra một dòng truyện tranh mới không ngừng," anh nói.

Bae cũng háo hức khám phá AI như một "pin dự phòng cho ý tưởng câu chuyện", giống như một trợ lý viết. Tuy nhiên, để giữ vững vị thế nghệ sĩ, anh dự định đào sâu hơn vào trí tưởng tượng của mình để tạo ra các ý tưởng độc đáo và thử nghiệm không thể tìm thấy ở nơi nào khác. "Đó là lĩnh vực của [người] sáng tạo," anh nói. Tuy nhiên, Bae tự hỏi liệu lợi thế sáng tạo của chính mình có dần phai nhạt thông qua sự hợp tác rộng rãi với AI không: "Liệu màu sắc của riêng tôi có bắt đầu mờ nhạt không?"

Trong khi đó, sinh viên truyện tranh tại Đại học Sejong ở Seoul đang học cách tích hợp AI vào bộ công cụ của họ. Các nghệ sĩ đang manh nha được đào tạo như "lập trình viên sáng tạo", biến các mẩu truyện tranh thành bộ dữ liệu bằng cách chú thích tỉ mỉ nội dung của chúng, và như các kỹ sư prompt người có thể hướng dẫn AI tạo ra các nhân vật phù hợp với cảm nhận thẩm mỹ của họ.

"Sáng tạo cần thời gian—để suy ngẫm và chiêm nghiệm về tác phẩm của bạn," Han Chang-wan, giáo sư truyện tranh và hoạt hình tại Đại học Sejong, người dạy một lớp về truyện tranh web do AI tạo ra, nói. Han nói đó là những gì AI sẽ mua cho sinh viên của ông: thời gian để "tạo ra nhiều nhân vật đa dạng hơn, cốt truyện đa sắc màu hơn và thể loại đa dạng hơn" thách thức những truyện tranh công thức do các studio sản xuất hàng loạt. Cuối cùng, ông hy vọng, họ sẽ "tiếp cận được một lượng độc giả hoàn toàn mới."

Khi các nghệ sĩ điều hướng tương lai chưa được khám phá này, AI generative đang đặt ra những câu hỏi sâu sắc về điều gì tạo nên sự sáng tạo. "AI có thể là trợ lý kỹ thuật cho các nghệ sĩ," Shin Il-sook, chủ tịch Hiệp hội Họa sĩ Truyện tranh Hàn Quốc và họa sĩ truyện tranh nổi tiếng đằng sau bộ truyện giả tưởng lịch sử lãng mạn The Four Daughters of Armian, theo chân một công chúa dũng cảm bị đày khỏi vương quốc mẫu hệ khi cô bắt đầu hành trình sinh tồn và tự khám phá thông qua chiến tranh, tình yêu và cuộc chiến quyền lực chính trị, nói. Tuy nhiên, bà tự hỏi liệu AI có thực sự có thể là một người bạn đồng hành sáng tạo không.

"Sáng tạo là việc tạo ra điều gì đó chưa từng thấy trước đây, được thúc đẩy bởi mong muốn chia sẻ nó với người khác," Shin nói. "Nó gắn chặt với trải nghiệm con người và những nỗi đau khổ của nó. Đó là lý do tại sao một nghệ sĩ đã trải qua những khổ đau của cuộc sống và rèn luyện nghề của mình tạo ra nghệ thuật xuất sắc," bà nói. "Bạn có thể sáng tạo mà không có linh hồn không? Ai biết được?"

Michelle Kim là nhà báo tự do và luật sư tại Seoul.

- Sony Music đã yêu cầu loại bỏ 75.000 deepfake, phản ánh quy mô của vấn đề này.

- Công ty bảo mật thông tin Pindrop cho biết nhạc do AI tạo ra có "dấu hiệu đặc trưng" và dễ phát hiện, tuy nhiên loại nhạc này dường như xuất hiện khắp nơi.

- Chỉ mất vài phút trên YouTube hoặc Spotify để phát hiện bản rap giả của 2Pac về pizza, hoặc bản cover của Ariana Grande cho một bài K-pop mà cô chưa từng thực hiện.

- Sam Duboff, người đứng đầu tổ chức chính sách của Spotify, cho biết họ đang nỗ lực phát triển công cụ mới để giải quyết vấn đề này tốt hơn.

- YouTube tuyên bố đang "hoàn thiện" khả năng phát hiện các bản sao AI và có thể công bố kết quả trong những tuần tới.

- Jeremy Goldman, nhà phân tích tại công ty Emarketer, nhận xét rằng "những kẻ xấu nhận thức được vấn đề sớm hơn", khiến nghệ sĩ, hãng đĩa và những người khác trong ngành âm nhạc "phải hoạt động từ vị thế phản ứng".

- Ngoài deepfake, ngành công nghiệp âm nhạc đặc biệt lo ngại về việc sử dụng nội dung của họ trái phép để huấn luyện các mô hình AI tạo sinh như Suno, Udio hoặc Mubert.

- Một số hãng thu âm lớn đã đệ đơn kiện công ty mẹ của Udio tại tòa án liên bang ở New York năm ngoái, cáo buộc họ phát triển công nghệ bằng cách sử dụng "bản ghi âm có bản quyền nhằm mục đích cuối cùng là chiếm đoạt người nghe, người hâm mộ và người cấp phép tiềm năng".

- Sau hơn 9 tháng, thủ tục tố tụng vẫn chưa thực sự bắt đầu. Điều tương tự cũng xảy ra với một vụ kiện tương tự chống lại Suno, được đệ trình ở Massachusetts.

- Trọng tâm của vụ kiện là nguyên tắc sử dụng hợp lý (fair use), cho phép sử dụng có giới hạn một số tài liệu có bản quyền mà không cần xin phép trước.

- Joseph Fishman, giáo sư luật tại Đại học Vanderbilt, gọi đây là "lĩnh vực thực sự không chắc chắn".

- Các phán quyết ban đầu có thể không mang tính quyết định, vì ý kiến khác nhau từ các tòa án khác nhau có thể đẩy vấn đề lên Tòa án Tối cao.

- Trong khi đó, các công ty lớn tham gia vào lĩnh vực âm nhạc do AI tạo ra tiếp tục huấn luyện mô hình của họ trên các tác phẩm có bản quyền.

- Trong lĩnh vực lập pháp, các hãng thu âm, nghệ sĩ và nhà sản xuất chưa đạt được nhiều thành công. Một số dự luật đã được đưa ra Quốc hội Mỹ, nhưng chưa có kết quả cụ thể.

- Donald Trump có thể là một trở ngại tiềm tàng khác: tổng thống Đảng Cộng hòa đã tự đặt mình là nhà vô địch của việc phi quy định hóa, đặc biệt là đối với AI.

- Meta đã kêu gọi chính quyền "làm rõ rằng việc sử dụng dữ liệu công khai để huấn luyện mô hình rõ ràng là sử dụng hợp lý".

- Tình hình ở Anh cũng không khả quan hơn, nơi chính phủ Công đảng đang xem xét cải cách luật để cho phép các công ty AI sử dụng nội dung của người sáng tạo trên internet để phát triển mô hình của họ, trừ khi chủ sở hữu quyền từ chối.

- Hơn một nghìn nhạc sĩ, bao gồm Kate Bush và Annie Lennox, đã phát hành một album vào tháng 2 có tên "Is This What We Want?" - với âm thanh im lặng được ghi lại trong một số studio - để phản đối những nỗ lực đó.

📌 Ngành âm nhạc đang trong cuộc chiến bất lợi với AI tạo sinh, với 75.000 deepfake đã bị Sony Music yêu cầu gỡ bỏ. Các nền tảng như YouTube và Spotify đang nỗ lực phát triển công cụ phát hiện, trong khi các vụ kiện pháp lý vẫn đang bế tắc và môi trường pháp lý còn nhiều bất cập.

https://technology.inquirer.net/141681/the-music-industry-is-battling-ai-with-limited-success

- Văn phòng Bản quyền Hoa Kỳ vừa công bố Phần 2 của Báo cáo về Bản quyền và AI, tập trung vào khả năng bảo hộ bản quyền cho các tác phẩm được tạo bởi AI.

- Báo cáo khẳng định rằng sự sáng tạo và vai trò tác giả của con người vẫn là yếu tố cốt lõi để được bảo hộ bản quyền cho các tác phẩm liên quan đến AI.

- Phần 1 của báo cáo đã thảo luận về các vấn đề pháp lý và chính sách liên quan đến AI và bản sao kỹ thuật số, trong khi Phần 2 phân tích loại và mức độ đóng góp của con người cần thiết để đưa tác phẩm AI vào phạm vi bảo hộ bản quyền.

- Văn phòng Bản quyền xác nhận rằng bảo hộ bản quyền tại Hoa Kỳ đòi hỏi tác giả phải là con người, dựa trên các nguyên tắc nền tảng từ Điều khoản Bản quyền trong Hiến pháp và ngôn ngữ của Đạo luật Bản quyền.

- Báo cáo nêu rõ 3 trường hợp tác phẩm AI có thể đủ điều kiện được bảo hộ bản quyền: sử dụng AI hỗ trợ, đầu vào biểu cảm và đầu ra tương ứng, và sửa đổi/sắp xếp nội dung do AI tạo ra.

- Văn phòng Bản quyền kết luận rằng các lệnh nhắc (prompts) đơn thuần không cung cấp đủ sự kiểm soát của con người để tự động biến người dùng AI thành tác giả của sản phẩm đầu ra.

- Báo cáo cũng đánh giá tình hình bảo hộ bản quyền cho tác phẩm AI trên toàn cầu, với các quốc gia như Liên minh Châu Âu, Vương quốc Anh, Nhật Bản và Trung Quốc có cách tiếp cận khác nhau.

- Văn phòng Bản quyền không thấy cần thiết phải có luật hoặc quy tắc mới để bảo vệ tác phẩm AI, cho rằng luật bản quyền hiện tại của Hoa Kỳ đủ linh hoạt để đáp ứng với công nghệ mới.

- Văn phòng bày tỏ lo ngại về tác động của tác phẩm AI đối với tác giả là con người và giá trị mà biểu đạt sáng tạo của họ mang lại cho xã hội, nhấn mạnh rằng "xã hội sẽ nghèo nàn hơn nếu tia lửa sáng tạo của con người trở nên ít hơn hoặc mờ nhạt hơn."

- Phần 3 sắp tới của báo cáo sẽ đề cập đến các hàm ý pháp lý của việc đào tạo mô hình AI trên các tác phẩm được bảo hộ bản quyền, các cân nhắc cấp phép và phân bổ trách nhiệm pháp lý tiềm ẩn.

📌 Văn phòng Bản quyền Hoa Kỳ khẳng định vai trò không thể thay thế của con người trong bảo hộ bản quyền cho tác phẩm AI. Chỉ có 3 trường hợp tác phẩm AI được bảo hộ: sử dụng AI hỗ trợ, đầu vào biểu cảm, và sửa đổi/sắp xếp nội dung AI. Prompts đơn thuần không đủ điều kiện bảo hộ.

https://www.reuters.com/legal/legalindustry/us-copyright-office-issues-highly-anticipated-report-copyrightability-ai-2025-04-02/

- Bài viết so sánh nghệ thuật được tạo bởi AI với ngành sản xuất snack để đề xuất cách tiếp cận mới trong việc điều chỉnh nội dung AI và bảo vệ nghệ sĩ.

- Tác giả chia sẻ kinh nghiệm cá nhân về việc nhận các túi snack từ người chú làm việc tại nhà máy sản xuất, cho thấy nhiều thương hiệu khác nhau thực chất đến từ cùng một dây chuyền sản xuất.

- CEO OpenAI Sam Altman tuyên bố nhu cầu sử dụng ChatGPT tăng cao đến mức "làm nóng" GPU, đặc biệt sau khi OpenAI cho phép trình tạo hình ảnh của họ sao chép nhiều tài sản trí tuệ không được cấp phép hơn.

- Các trình tạo hình ảnh AI mới chia hình ảnh thành các token và dự đoán các yếu tố phù hợp nhất, tạo ra các cảnh theo phong cách thống nhất, nhưng luật pháp quốc tế chưa xác định liệu việc tokenization này có vi phạm bản quyền của tài liệu huấn luyện hay không.

- Hiện tượng "Ghiblified" xuất hiện khi ChatGPT cho phép người dùng tạo hình ảnh theo phong cách Studio Ghibli - hãng hoạt hình Nhật Bản nổi tiếng với ngôn ngữ hình ảnh được phát triển trong 40 năm.

- Xu hướng này nhanh chóng bị lạm dụng trên internet, với những hình ảnh gây sốc như vụ 11/9 hay cảnh bắt giữ được vẽ theo phong cách Ghibli, thậm chí có cả hình ảnh của nhà đồng sáng lập Hayao Miyazaki nói rằng nghệ thuật có sự hỗ trợ của máy tính là "xúc phạm đến cuộc sống".

- Tác giả đề xuất áp dụng nguyên tắc "passing-off" từ quy định về nhãn hiệu riêng: một sản phẩm có thể giống sản phẩm khác miễn là không lợi dụng danh tiếng và thiện chí của người sáng tạo.

- AI tạo sinh không thực sự là sáng tạo mà là tiêu thụ - người dùng không muốn tạo ra thứ gì đó, họ chỉ muốn có được thứ gì đó. Máy móc không phát minh, nó chỉ lắp ráp.

- Xu hướng Ghibli nhanh chóng mất đi sức hút sau khi bắt đầu với các phiên bản nhại của hình ảnh nổi tiếng, sau đó chuyển sang giá trị gây sốc và cuối cùng không còn đi đến đâu.

- Sam Altman thừa nhận ChatGPT đã thêm một triệu người dùng mới trong một giờ sau khi quảng bá trò Ghibli, điều mà tác giả cho rằng nghe giống như một lời thú nhận.

📌 Thay vì tập trung vào cách thức sản xuất, nên đánh giá nghệ thuật AI dựa trên diện mạo và việc lợi dụng danh tiếng. Trường hợp Studio Ghibli cho thấy AI không thực sự sáng tạo mà chỉ lắp ráp, và OpenAI đã thu hút 1 triệu người dùng mới trong 1 giờ bằng cách khai thác phong cách nghệ thuật đã được xây dựng trong 40 năm.

https://www.ft.com/content/1674e431-5f4a-4952-8ea1-2e9add47abaf

#FT

Để tìm cách tốt hơn nhằm quản lý nghệ thuật AI và bảo vệ nghệ sĩ, hãy nhìn vào khoai tây chiên

Đánh giá sản phẩm dựa trên diện mạo, không phải cách thức tạo ra nó

Bryce Elder

Bài viết này nói về nghệ thuật được tạo ra bởi AI và khoai tây chiên, bắt đầu với cái quan trọng hơn trong hai thứ.

Mỗi tháng, chú tôi cho tôi một túi rác đầy khoai tây chiên. Nhân viên tại nhà máy sản xuất khoai tây chiên nơi chú làm việc có thể lấy nhiều khoai tây chiên tràn ra khỏi máng chuyền, vì vậy mỗi lần lấy là một tổng hợp ngẫu nhiên đại diện cho xu hướng đồ ăn nhẹ từ khoai tây chiên của Anh. Túi tháng này bao gồm khoai tây chiên từ 2 trong số 4 siêu thị lớn, một cửa hàng giảm giá của Đức và một cửa hàng bán sandwich có tầm quan trọng chiến lược quốc gia. Tất cả đều rơi ra từ cùng một dây chuyền sản xuất.

Điều đó không có nghĩa là chúng giống hệt nhau. Giấm có thể là giấm mạch nha hoặc giấm táo. Phô mai đôi khi được gắn với một chỉ định địa lý, và cách hiểu về "muối vừa đủ" so với "muối nhẹ" đáng được nghiên cứu học thuật. Điều tôi có thể nói với hiểu biết hiếm có là, bất kể bao bì nói gì, những khác biệt như vậy không đáng kể. Khoai tây chiên là khoai tây chiên.

Khoai tây chiên kiểu Mỹ thì khác biệt, nhưng cũng có thể được chiên. Giám đốc điều hành OpenAI Sam Altman tuyên bố tuần này rằng nhu cầu về bot ChatGPT của họ cao đến mức làm nóng GPU. Số lượng người dùng tăng vọt sau khi OpenAI cho phép trình tạo hình ảnh của mình sao chép một vũ trụ rộng lớn hơn về sở hữu trí tuệ chưa được cấp phép.

Cách thức hoạt động của nó không thú vị lắm, đó là lý do tại sao chúng ta bắt đầu với khoai tây chiên. Tóm lại: các trình tạo hình ảnh AI đầu tiên xếp từng pixel riêng lẻ. Loại mới hơn chia hình ảnh thành các token và dự đoán những yếu tố nào phù hợp nhất với nhau, do đó có thể tạo ra cảnh theo một phong cách thống nhất. Luật pháp quốc tế chưa giải quyết xong liệu loại tokenization này có vi phạm bản quyền của các tài liệu huấn luyện hay không, và OpenAI không chờ đợi để tìm hiểu. Thông qua việc ưu tiên cái có thể thực hiện được hơn là cái có trách nhiệm, một từ mới đã được thêm vào từ vựng văn hóa của chúng ta: "Ghiblified" (được Ghibli hóa).

Từ này ám chỉ Studio Ghibli, hãng phim hoạt hình Nhật Bản nổi tiếng với ngôn ngữ hình ảnh được chế tác trong hơn 40 năm với nhiều lớp cảm xúc như các câu chuyện của họ. ChatGPT đã làm cho phong cách Ghibli lai tạp có sẵn thông qua các lệnh văn bản đơn giản và, đây là internet, mọi thứ diễn ra đúng như bạn mong đợi.

Meme Ghibli trong vòng vài giờ đã tụt xuống giá trị gây sốc, sau đó không còn đi đâu được nữa

Bạn có bao giờ muốn thấy vụ 11/9 được thể hiện bằng màu pastel nhẹ nhàng của Nhật Bản? Hoặc một sĩ quan Mỹ còng tay một người phụ nữ đang khóc nức nở, được định kiểu để trông giống một cảnh từ Porco Rosso? Chúng tôi có thể làm bạn quan tâm đến một bộ phim hoạt hình được tái tạo máy móc về Hayao Miyazaki, người đồng sáng lập được tôn kính của Ghibli, nói với xưởng phim rằng nghệ thuật có sự hỗ trợ của máy tính là "một sự xúc phạm đối với cuộc sống"? Có lẽ là không, nhưng bất kỳ ai trực tuyến trong 2 tuần qua đều không có sự lựa chọn.

Đến lúc này, bạn có thể đang tự hỏi điều này có liên quan gì đến khoai tây chiên.

Việc AI thu thập sở hữu trí tuệ có sự tương đồng trong quy định về nhãn hiệu riêng. Không có bản quyền cho phong cách - một nhà sản xuất đồ ăn nhẹ không thể tuyên bố sử dụng độc quyền một hương vị cũng như một nghệ sĩ không thể đăng ký bản quyền cho một phong cách, ví dụ vậy - nhưng luật liên quan ở Anh và nơi khác, gọi là "passing-off" (mạo danh), vẫn tìm cách ngăn chặn việc sao chép sử dụng các đặc điểm riêng biệt của một thương hiệu khác theo cách có thể gây nhầm lẫn hoặc đánh lừa khách hàng.

Một sản phẩm có thể giống với sản phẩm khác miễn là không ăn theo danh tiếng và thiện chí của người sáng tạo ra nó. Và mặc dù các vụ kiện mạo danh hiếm khi thành công, đã có đủ tiền lệ được thiết lập để các công ty biết giới hạn. Khoai tây chiên trong ống: có lẽ không sao. Người đàn ông có ria mép trên ống: có lẽ không được.

Tôi đề xuất bảo vệ nghệ sĩ nhiều như bảo vệ nhà sản xuất khoai tây chiên. Đánh giá sản phẩm dựa trên diện mạo, không phải cách thức tạo ra nó.

Điểm xuất phát sai lầm khi cố gắng hiểu AI tạo sinh là coi những gì nó làm là sáng tạo. Không phải vậy. Đó là tiêu thụ. Người dùng không muốn tạo ra thứ gì đó, họ muốn có thứ gì đó. Máy móc không phát minh, nó lắp ráp. Đó là dây chuyền sản xuất của một nhà sản xuất hàng hóa.

Để chứng minh, hãy nhìn vào quỹ đạo của meme Ghibli. Nó bắt đầu với các bản parody của những hình ảnh nổi tiếng, trong vòng vài giờ đã tụt xuống giá trị gây sốc, sau đó không còn đi đâu được nữa. Trong số những người luôn trực tuyến, những người có vị trí tốt nhất để học và nhận biết cách vận hành cụ thể của một nhà máy nội dung, tính mới lạ đã mất đi trong chưa đầy một ngày.

Hầu hết các đột phá AI phi khoa học dường như chấm dứt theo cách này. Gần như không có gì được tạo ra bởi thuật toán để lại ấn tượng lâu dài, có lẽ vì không có sự sống nào tham gia vào quá trình tạo ra nó. Nghệ thuật tạo sinh là một sự mâu thuẫn.

Trong khi đó, khoai tây chiên là khoai tây chiên. Thật quá dễ dàng để bị sa lầy trong triết lý về việc liệu mã hóa một tác phẩm nghệ thuật mà không bồi thường cho người sáng tạo ra nó có phải là hành vi trộm cắp hay không. Một câu hỏi tốt hơn liên quan đến việc liệu ai đó đang tìm cách kiếm lợi từ danh tiếng và thiện chí khó kiếm được của người khác. Chỉ cần nhìn vào sản phẩm là đủ để biết.

Sau khi ủng hộ và quảng bá cho màn trình diễn Ghibli, Altman cho biết ChatGPT đã thêm một triệu người dùng mới trong một giờ. Đặt trong bối cảnh đúng đắn, nó nghe giống như một lời thú nhận.

Bryce Elder là Biên tập viên Thành phố của FT, Alphaville

For a better way to regulate AI art and protect artists, look at crisps

- Tòa án liên bang Mỹ đã quyết định hợp nhất 12 vụ kiện bản quyền chống lại OpenAI và Microsoft tại New York, bất chấp việc đa số nguyên đơn phản đối việc tập trung này.

- Hội đồng tư pháp Mỹ về tranh chấp đa khu vực đã ra lệnh chuyển giao vào ngày 4/4/2025, cho rằng việc hợp nhất sẽ "cho phép một thẩm phán duy nhất điều phối quá trình thu thập bằng chứng, hợp lý hóa các thủ tục trước khi xét xử và loại bỏ các phán quyết không nhất quán".

- Các vụ kiện từ California do các tác giả nổi tiếng như Ta-Nehisi Coates, Michael Chabon, Junot Díaz và Sarah Silverman sẽ được chuyển đến New York và kết hợp với các vụ kiện từ các cơ quan truyền thông như New York Times và các tác giả khác như John Grisham, George Saunders, Jonathan Franzen và Jodi Picoult.

- Lệnh chuyển giao nêu rõ các vụ kiện "chia sẻ các câu hỏi thực tế phát sinh từ cáo buộc rằng OpenAI và Microsoft đã sử dụng các tác phẩm có bản quyền, mà không có sự đồng ý hoặc bồi thường, để huấn luyện các mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn (LLMs) của họ".

- Các công ty công nghệ lập luận rằng việc họ sử dụng tác phẩm có bản quyền để huấn luyện AI được cho phép theo học thuyết "sử dụng hợp lý", cho phép sử dụng trái phép các tác phẩm có bản quyền trong một số trường hợp nhất định.

- Người phát ngôn OpenAI hoan nghênh quyết định này và mong muốn làm rõ tại tòa rằng "các mô hình của họ được huấn luyện trên dữ liệu công khai, dựa trên sử dụng hợp lý và hỗ trợ đổi mới".

- Nhiều tác giả nổi tiếng kiện OpenAI cũng đã kiện Meta vì vi phạm bản quyền trong việc huấn luyện các mô hình AI. Hồ sơ tòa án tháng 1 cáo buộc CEO Meta Mark Zuckerberg đã phê duyệt việc công ty sử dụng "thư viện bóng tối" LibGen, chứa hơn 7,5 triệu cuốn sách.

- Vào ngày 4/4, các tác giả đã tập trung bên ngoài văn phòng Meta ở London để phản đối việc công ty sử dụng sách có bản quyền, với các biểu ngữ như "Get the Zuck off our books" và "I'd write a better sign but you'd just steal it".

- Cùng ngày, Amazon xác nhận tính năng mới "Recaps" trên Kindle, cung cấp cho người dùng bản tóm tắt cốt truyện và nhân vật của một bộ sách, sẽ được tạo ra bởi AI.

- Tuần này, chính phủ Anh đang cố gắng xoa dịu các lo ngại từ các nghị sĩ về đề xuất bản quyền của mình - cho phép các công ty AI huấn luyện mô hình trên tài liệu có bản quyền trừ khi chủ sở hữu quyền từ chối.

📌 Cuộc chiến pháp lý về bản quyền trong lĩnh vực AI đang leo thang với việc hợp nhất 12 vụ kiện tại New York. Các tác giả và nhà xuất bản đấu tranh bảo vệ quyền lợi trước việc OpenAI, Microsoft và Meta sử dụng nội dung có bản quyền để huấn luyện AI, trong khi các công ty công nghệ viện dẫn nguyên tắc "sử dụng hợp lý".

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/apr/04/us-authors-copyright-lawsuits-against-openai-and-microsoft-combined-in-new-york-with-newspaper-actions

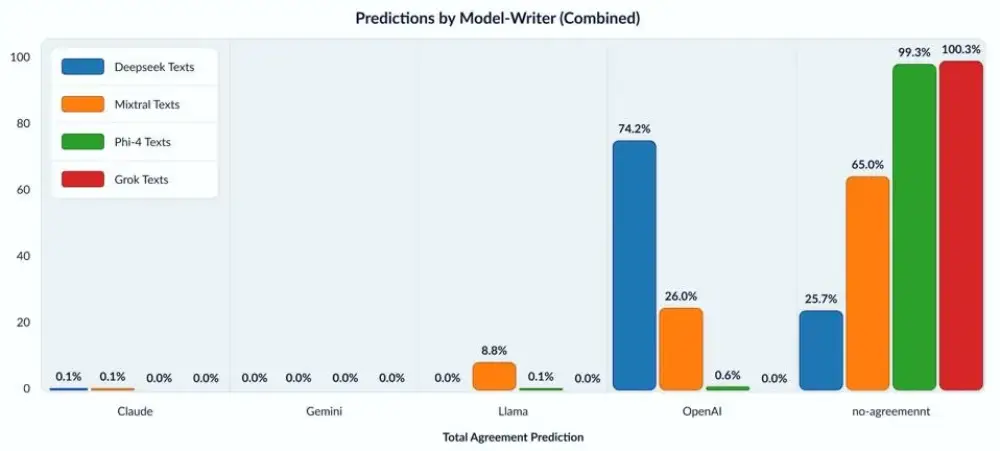

- Một nghiên cứu mới từ các nhà khoa học tại Đại học Washington, Đại học Copenhagen và Stanford đưa ra bằng chứng cho thấy OpenAI đã huấn luyện mô hình AI của mình trên nội dung có bản quyền.

- OpenAI hiện đang đối mặt với nhiều vụ kiện từ tác giả, lập trình viên và chủ sở hữu bản quyền khác, cáo buộc công ty sử dụng tác phẩm của họ (sách, mã nguồn...) để phát triển mô hình AI mà không xin phép.

- Nghiên cứu đề xuất phương pháp mới để xác định dữ liệu huấn luyện đã được "ghi nhớ" bởi các mô hình AI thông qua API, như của OpenAI.

- Phương pháp này dựa trên các từ được gọi là "high-surprisal" (từ ngữ bất ngờ cao) - những từ nổi bật vì không phổ biến trong ngữ cảnh của một tác phẩm lớn hơn.

- Các nhà nghiên cứu đã kiểm tra nhiều mô hình của OpenAI, bao gồm GPT-4 và GPT-3.5, bằng cách xóa các từ ngữ bất ngờ cao khỏi đoạn trích từ sách tiểu thuyết và bài báo của New York Times, sau đó yêu cầu mô hình "đoán" từ nào đã bị che.

- Kết quả cho thấy GPT-4 có dấu hiệu ghi nhớ các phần của sách tiểu thuyết phổ biến, bao gồm sách trong bộ dữ liệu BookMIA chứa các mẫu sách điện tử có bản quyền.

- Kết quả cũng cho thấy mô hình đã ghi nhớ các phần của bài báo New York Times, mặc dù ở tỷ lệ thấp hơn so với sách.

- Abhilasha Ravichander, nghiên cứu sinh tiến sĩ tại Đại học Washington và đồng tác giả của nghiên cứu, cho biết phát hiện này làm sáng tỏ về "dữ liệu gây tranh cãi" mà các mô hình có thể đã được huấn luyện.

- OpenAI từ lâu đã ủng hộ việc nới lỏng các hạn chế về phát triển mô hình sử dụng dữ liệu có bản quyền, đồng thời vận động hành lang nhiều chính phủ để luật hóa quy tắc "sử dụng hợp lý" đối với phương pháp huấn luyện AI.

- Mặc dù OpenAI có một số thỏa thuận cấp phép nội dung và cung cấp cơ chế cho phép chủ sở hữu bản quyền đánh dấu nội dung họ không muốn công ty sử dụng cho mục đích huấn luyện, vấn đề pháp lý về việc sử dụng dữ liệu có bản quyền vẫn còn gây tranh cãi.

📌 Nghiên cứu từ ba đại học danh tiếng đã phát hiện GPT-4 và GPT-3.5 "ghi nhớ" nội dung có bản quyền từ sách và báo chí. Phương pháp dùng "từ ngữ bất ngờ cao" cho thấy OpenAI có thể đã huấn luyện mô hình trên dữ liệu có bản quyền, làm gia tăng tranh cãi pháp lý hiện tại.

https://techcrunch.com/2025/04/04/openais-models-memorized-copyrighted-content-new-study-suggests/

- Chính phủ Anh đang nỗ lực xoa dịu những lo ngại từ các nghị sĩ và nghị viện về đề xuất bản quyền bằng cách cam kết đánh giá tác động kinh tế của kế hoạch này.

- Các chuyên gia sáng tạo nổi tiếng như Sir Paul McCartney, Sir Tom Stoppard và Kate Bush đã mạnh mẽ chỉ trích đề xuất cho phép các công ty AI huấn luyện mô hình của họ trên tác phẩm được bảo vệ bản quyền mà không cần xin phép, trừ khi chủ sở hữu quyền từ chối.

- Lập trường này đã nhận được sự ủng hộ từ các nghị sĩ, những người đã thông qua các sửa đổi phản đối đề xuất, và từ một số nghị sĩ hậu thuẫn.

- Các nhượng bộ được đề xuất cho nghị sĩ và các nghị viên trong tuần này bao gồm đánh giá tác động kinh tế, với báo cáo có thể giải quyết các vấn đề như cách nhà phát triển AI truy cập dữ liệu để đào tạo mô hình và tính minh bạch xung quanh việc sử dụng tác phẩm được bảo vệ bản quyền.

- Các bộ trưởng hy vọng những nhượng bộ này sẽ cho phép dự luật dữ liệu (sử dụng và truy cập) được thông qua. Dự luật đã được sử dụng như một phương tiện để chống lại các đề xuất nhưng hiện có thể bị mắc kẹt trong một quá trình được gọi là "ping pong", nơi một dự luật được chuyển qua lại giữa Thượng viện và Hạ viện.

- Beeban Kidron, nghị sĩ đã thành công đưa ra các sửa đổi cho dự luật để chống lại các đề xuất, cho rằng Bộ Khoa học, Đổi mới và Công nghệ "gần như hoàn toàn" tập trung vào lợi ích của các nhóm vận động hành lang công nghệ Mỹ.

- James Frith, thành viên Đảng Lao động của ủy ban văn hóa, truyền thông và thể thao, cho biết ông vẫn được khuyến khích bởi cam kết đối thoại của chính phủ, nhưng cần có sự minh bạch hoàn toàn về cách sử dụng tác phẩm được bảo vệ bản quyền và việc sử dụng tài liệu đó cần được bồi thường.

- Người phát ngôn chính phủ cho biết họ đang xem xét cẩn thận các phản hồi tham vấn và tiếp tục tương tác với các công ty công nghệ, ngành công nghiệp sáng tạo và quốc hội để định hình cách tiếp cận của họ.

- Chính phủ dự kiến sẽ công bố phản hồi của mình đối với cuộc tham vấn về các đề xuất vào mùa hè hoặc trước tháng 10.

📌 Chính phủ Anh đang phải nhượng bộ trước làn sóng phản đối mạnh mẽ từ các nghệ sĩ nổi tiếng như Paul McCartney về dự luật bản quyền AI. Họ cam kết đánh giá tác động kinh tế và tăng tính minh bạch, nhưng vẫn chưa đưa ra quyết định cuối cùng cho đến mùa hè hoặc tháng 10 năm 2025.

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/apr/02/uk-government-tries-to-placate-opponents-of-ai-copyright-bill

- Giám đốc điều hành Channel 4, Alex Mahon, cảnh báo rằng các công ty AI đang "hút giá trị" từ ngành công nghiệp sáng tạo trị giá 125 tỷ bảng của Vương quốc Anh.

- Mahon phát biểu trước các nghị sĩ rằng nếu chính phủ theo đuổi kế hoạch cho phép các công ty AI tiếp cận tác phẩm sáng tạo trừ khi chủ sở hữu bản quyền từ chối (opt-out), điều này sẽ đặt ngành công nghiệp sáng tạo Anh vào "vị thế nguy hiểm".

- Các nhà phê bình đề xuất opt-out của chính phủ, được đưa ra trong một cuộc tham vấn kết thúc vào tháng 2, cho rằng nó không công bằng và không thực tế.

- Các mô hình AI tạo sinh được đào tạo trên lượng dữ liệu khổng lồ để tạo ra các phản hồi cực kỳ thực tế.

- Mahon cho biết việc cho phép các mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn (LLM) tiếp tục tự do thu thập dữ liệu gây ra mối đe dọa lớn đối với ngành công nghiệp sáng tạo, tạo ra 125 tỷ bảng giá trị gia tăng gộp (GVA).

- Ngành công nghiệp sáng tạo chiếm 6% GVA của Vương quốc Anh và đang tăng trưởng nhanh hơn 1,5 lần so với các lĩnh vực khác.

- Các tác giả, nghệ sĩ và giám đốc điều hành từ ngành công nghiệp phim và truyền hình đã lập luận rằng việc cho phép các công ty đào tạo chương trình AI trên tác phẩm của họ mà không có giấy phép đe dọa sinh kế của họ.

- Channel 4 ủng hộ chế độ bản quyền "opt-in", đặt gánh nặng lên các công ty AI, không phải lên các nhà sáng tạo nội dung.

- Mahon cũng cho biết Channel 4 đã hòa vốn trong năm ngoái, cải thiện so với khoản thâm hụt 52 triệu bảng năm 2023.

- Bà cũng cảnh báo rằng các quy định về sự nổi bật của chương trình phát sóng dịch vụ công cộng (PSB) như Channel 4, BBC và ITV có thể cần được mở rộng sang các nền tảng mới, bao gồm cả nền tảng xã hội.

📌 Các công ty AI đang khai thác giá trị từ ngành sáng tạo Anh trị giá 125 tỷ bảng mà không trả phí bản quyền. Channel 4 kêu gọi chuyển từ cơ chế "opt-out" sang "opt-in", buộc các công ty AI phải cấp phép và trả tiền cho nội dung họ sử dụng để bảo vệ ngành đang tăng trưởng nhanh gấp 1,5 lần các lĩnh vực khác.

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/apr/01/ai-firms-scraping-value-uk-creative-industries-says-channel-4-boss-alex-mahon

-

Grant Slatton, kỹ sư sáng lập tại Row Zero, đã sử dụng tính năng tạo hình ảnh của OpenAI's 4o để tạo ra phiên bản Studio Ghibli từ một bức ảnh, khởi đầu cho xu hướng vẫn đang phát triển mạnh mẽ.

-

OpenAI gần đây đã giới thiệu tính năng tạo hình ảnh tích hợp trong GPT-4o, cho phép người dùng tạo nhiều loại hình ảnh như infographic, truyện tranh, biển báo, đồ họa, thực đơn, meme và nhiều hơn nữa.

-

Xu hướng này đặt ra nhiều câu hỏi quan trọng về khả năng mô phỏng phong cách nghệ thuật của Studio Ghibli và vấn đề bản quyền liên quan.

-

Theo DeepLearning.AI, luật pháp Nhật Bản cho phép các nhà phát triển huấn luyện mô hình AI trên các tài liệu được bảo vệ bản quyền.

-

Năm 2024, Cơ quan Văn hóa Nhật Bản đã công bố tài liệu "Hiểu biết chung về AI và bản quyền tại Nhật Bản", giải thích khi nào luật bản quyền có hiệu lực và khi nào dữ liệu có thể được sử dụng cho AI.

-

Tài liệu này nêu rõ việc sử dụng tác phẩm có bản quyền không nhằm mục đích thưởng thức có thể được phép mà không cần sự cho phép của chủ sở hữu bản quyền.

-

Bảo hộ bản quyền áp dụng cho "biểu đạt sáng tạo" của một ý tưởng chứ không phải bản thân ý tưởng đó, nên tài liệu do AI tạo ra áp dụng "phong cách của người sáng tạo" không vi phạm bản quyền nếu phong cách đó chỉ bao gồm một ý tưởng.

-