ChatGPT bị coi là “ngốn điện”, nhưng phát thải cá nhân từ AI rất nhỏ so với TV, lưu trữ số hay đi lại hằng ngày

-

AI bị gắn mác “ngốn điện”: một câu hỏi ChatGPT tiêu tốn gấp 10 lần điện so với tìm kiếm Google; một ảnh AI tương đương sạc điện thoại; một clip 5 giây tiêu thụ 944 Wh (tương đương đạp xe e-bike 61 km).

-

Nghiên cứu của Planet FWD cho thấy cá nhân khó tạo phát thải lớn từ AI: 8 câu hỏi AI/ngày trong một năm chỉ chiếm 0,003% lượng phát thải trung bình của một người Mỹ.

-

Phát thải số chủ yếu đến từ: xem TV (104,5 kg CO₂/năm), internet máy tính (28,5 kg), lưu trữ dữ liệu (25,9 kg), trong khi AI queries chỉ 0,5 kg.

-

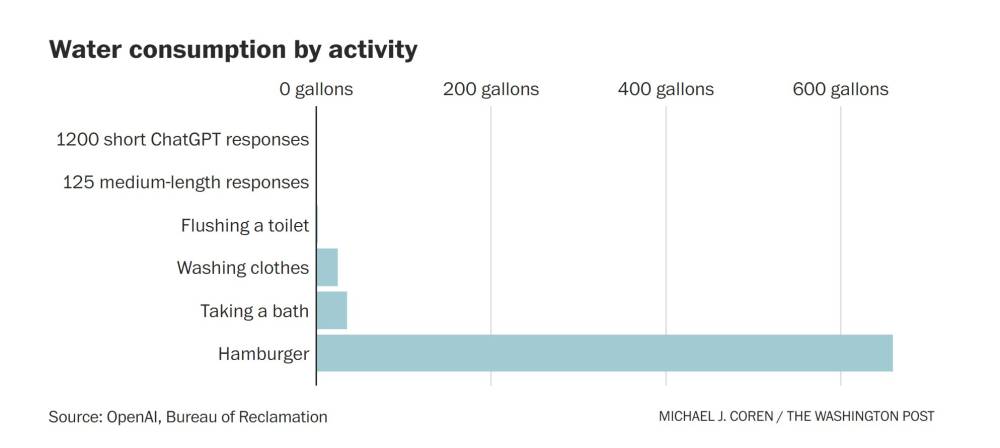

AI tiết kiệm nước so với các hoạt động thường ngày: một câu hỏi ChatGPT tiêu tốn 0,000085 gallon nước (~1/15 thìa cà phê), ít hơn nhiều so với việc xả bồn cầu, giặt đồ hay ăn hamburger (660 gallons).

-

Hiệu suất AI cải thiện rõ: từ 7–9 Wh mỗi câu hỏi năm 2023 xuống 0,3 Wh hiện tại (Gemini ~0,24 Wh). Google báo cáo giảm 44 lần chỉ trong một năm.

-

Tuy nhiên, sự bùng nổ nhu cầu AI đang kéo theo tăng trưởng dữ liệu: Goldman Sachs dự báo trung tâm dữ liệu tiêu thụ 8% điện Mỹ vào 2030 (so với 3% hiện nay).

-

OpenAI với “Stargate Project” đầu tư 500 tỷ USD xây 20 trung tâm dữ liệu, có cơ sở kèm nhà máy khí đốt 360 MW, bằng công suất một thành phố trung bình.

-

Xu hướng “hiệu suất càng cao, tiêu thụ càng nhiều” lặp lại giống Cách mạng công nghiệp: năng lượng tiết kiệm lại đổ vào các mô hình lớn hơn, đa dụng hơn.

-

Các nguồn năng lượng sạch (gió, mặt trời) chậm mở rộng do chính sách, trong khi hạt nhân và nhiệt hạch còn xa thương mại hóa.

-

Hệ quả: cư dân ở những vùng như Virginia có thể phải gánh chi phí điện cao hơn, đối mặt với không khí ô nhiễm hơn do mở rộng trung tâm dữ liệu.

-

Sam Altman (OpenAI) khẳng định “trí tuệ rẻ đến mức không cần tính phí” sẽ đến khi chi phí hội tụ về giá điện, gợi lại viễn cảnh “too cheap to meter” từng thất bại trong ngành hạt nhân.

📌 Dữ liệu cho thấy phát thải từ AI cá nhân cực nhỏ: 8 câu hỏi ChatGPT/ngày chỉ bằng 0,003% dấu chân carbon của người Mỹ, trong khi xem tivi gây hơn 100 kg CO₂/năm. Thách thức lớn nằm ở quy mô: trung tâm dữ liệu có thể ngốn 8% điện Mỹ vào 2030, với các dự án khổng lồ như OpenAI Stargate. Nếu không kiểm soát, lợi ích AI có nguy cơ bị lu mờ bởi sự phụ thuộc năng lượng hóa thạch và chi phí xã hội tăng cao.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2025/08/26/ai-climate-costs-efficiency/

ChatGPT is an energy guzzler. These things you’re doing are worse.

AI services have earned a reputation as energy-hungry beasts. But what about the other emissions in our digital lives?

As researchers scrutinize Big Tech’s utility bills, artificial intelligence has earned a reputation as a thirsty, energy-hungry beast. A single Q&A session with a large language model (LLM) can consume more than a half-liter of fresh water to cool servers. Asking ChatGPT one question reportedly consumes 10 times as much electricity as a conventional Google search. And generating an image is equivalent to charging a smartphone.

But should we worry about it?

Five years ago, there was a similar panic over streaming video. A frenzy followed a French think tank’s estimates that streaming a half-hour Netflix show generated as much CO2 as driving almost four miles. Globally, this implied, the streaming giant was consuming enough electricity annually to power Britain in service of shows like “Tiger King.”

But it turned out that those estimates relied on faulty assumptions about the energy use of data centers and streaming video. The actual emissions, former International Energy Agency analyst George Kamiya calculated, were 25 to 53 times lower.

As AI commandeers more of our digital lives, it’s worth asking again: Is this technology as voracious as we fear? If so, what can we do about it?

So I teamed up with decarbonization analytics company Planet FWD. We analyzed the emissions associated with our digital lives, and what role AI is playing as we pelt it with questions billions of times per day.

Individuals asking LLMs questions, our data suggests, is not the problem. Text responses don’t consume much energy. But AI’s integration into almost everything from customer service calls to algorithmic “bosses” to warfare is fueling enormous demand. Despite dramatic efficiency improvements, pouring those gains back into bigger, hungrier models powered by fossil fuels will create the energy monster we imagine.

Here’s what AI means for the emissions of our digital lives.

A robot eating a search bar.

AI emits more than search

There’s no question that AI queries consume more energy than Google’s search bar, even as the two have begun to merge. It takes a massive amount of energy to build an LLM and then incrementally more to process requests. How much more?

In 2023, Netherlands researcher Alex de Vries put the number at 23 to 30 times as much energy as conventional search, or roughly 7 to 9 watt-hours (Wh), enough to power a standard LED lightbulb for about an hour. The International Energy Agency lowered its estimate a year later to 2.9 Wh of electricity per ChatGPT query, roughly 10 times that of a comparable Google Search.

Since then, the figure has fallen to 0.3 Wh, according to AI research firm Epoch AI, a discrepancy attributed to smaller, more efficient models. Google confirmed by email that its median text response by its AI tool Gemini used slightly less, 0.24 Wh.

These numbers are not definitive: AI research firms have resisted releasing independently verified emissions data, and factors such as model size, reasoning capacity, electricity mix and query request (text, image or video) mean emissions can vary more than 50-fold. De Vries called his estimation process “grasping at straws.”

But the trend is clear: massive efficiency gains. Google claims emissions from a Gemini text response fell by a factor of 44 over the last year.

A burger eating a robot with a search bar.

AI is a tiny part of our digital footprint — for now

You’d be hard-pressed to ask enough questions to ChatGPT, Perplexity or other AI services to meaningfully change your personal emissions. Asking AI eight simple text questions a day, every day of the year, adds up to less than 0.1 ounces of climate pollution, our data suggests. That’s 0.003 percent of the average American’s annual carbon footprint.

More involved responses will consume more energy, but it’s still less than a rounding error on your annual accounts. The exception is AI-generated video: one five-second clip requires 944 Wh, equivalent to riding 38 miles on an e-bike.

Overall, our personal and work-related digital emissions are dominated by just three things: TV, digital storage and internet or video use on your computer. Why is TV such an energy hog? Americans tend to watch a lot of TV — 4.5 hours daily — and big screens suck up electricity for high-quality display and streaming, even when they’re in standby mode.

Personal GHG emissions from digital activities for a typical American per year

Personal digital activitiesWork digital activities

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Standard search (8/day)

0.1

AI image creation (1/day)

0.1

AI queries

0.5

App and web use (tablet)

1.8

App and web use (smartphone)

3.4

Video streaming (computer)

25.1

Digital storage

25.9

Internet use (computer)

28.5

TV viewing

104.5

Emissions in kilograms CO2 equivalent. Illustrative user based on time-use/technology surveys from Nielsen, DataReportal, U.S. Census Bureau. Assumes eight AI/search; one image query per day

Source: Source: PlanetFWD, published estimates in the scientific literature

Michael J. Coren / THE WASHINGTON POST

What about water? Data centers are thirsty. But so are cattle. If you were to eat a hamburger, for example, it would take 660 gallons to get it on your plate, bun and all. ChatGPT is a comparative teetotaler consuming 0.000085 gallons of water, or one-fifteenth of a teaspoon, per response, claims the company, roughly in line with outside researchers’ estimates. Google estimates Gemini, its AI tool, consumes even less (or about five drops) of water per text request.

Water consumption by activity

0 gallons

200 gallons

400 gallons

600 gallons

1200 short ChatGPT responses

125 medium-length responses

Flushing a toilet

Washing clothes

Taking a bath

Hamburger

Source: OpenAI, Bureau of Reclamation

Michael J. Coren / THE WASHINGTON POST

This gets to the truism about where we, as individuals, can see the biggest bang for our emissions buck: what we eat, how we move around and how we heat or cool our homes.

Nothing in your digital life, for example, comes close to your commute. For the average car-driving American, going back and forth to work emits at least eight times more than digital activities for work and personal combined (another argument against return to office).

Annual GHG emissions by activity for a typical American

0 kg CO2e

500 kg CO2e

1,000 kg CO2e

1,500 kg CO2e

Search queries

AI queries

Digital storage

Work digital activities

Personal digital activities

Average U.S. commute

Assumes eight AI/search; one image query per day. Assumes representative avg. of commuting modes: car, transit, motorcycle, bike, walking.

Source: Neilson, DataReportal, U.S. Census Bureau, DOT

Michael J. Coren / THE WASHINGTON POST

“We sometimes lose the perspective that a lot of these technological advances actually allow for a ton of increased efficiency, so we maybe don’t always want to demonize them,” said Miranda Gorman, who leads Planet FWD’s climate solutions practice. “If you can work from home instead of driving a car, the emissions from working from home then seem pretty small.”

A robot eating the earth.

Of data centers and power plants

I don’t want to downplay this. Our individual emissions are small, but AI’s demands on our electricity are enormous. It’s the biggest driver in the growth of data centers, which are expected to consume 8 percent of total electricity in the United States by 2030, up from 3 percent today, according to a recent Goldman Sachs analysis.

Many of the 8.2 billion people on the planet will want — and get — access to AI services on any device that supports it. Companies and governments are investing hundreds of billions in the technology to claim an edge.

Imagine the future, just around the corner, when AI is everywhere. Companies ping AI agents billions of times daily to provide basic services. Doctors have one in every consultation. A virtual assistant on your phone listens and responds to requests for hours a day. Complex, energy-hungry videos crowd our social feeds.

As all of this starts to happen right now, where does that leave us?

AI companies have trumpeted enormous strides in energy efficiency. And it’s true that chips powering today’s AI algorithms consume less than 1 percent of the energy required for the same amount of computing power in 2008. Vijay Gadepally, a senior scientist at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, found that simple fixes — more efficient hardware, streamlined training models and timing energy consumption to periods of renewable energy generation — could shave up to 20 percent off global data center demand, while slashing emissions of certain operations by at least 80 percent.

But it won’t be enough. As efficiency improves, we often consume more, not less — a paradox first observed in coal-burning England during the Industrial Revolution. “As AI gets more efficient and accessible,” wrote Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella on X this year, “we will see its use skyrocket, turning it into a commodity we just can’t get enough of.”

New energy sources are being brought online as fast as possible — much of it far dirtier than the new grid capacity added each year (96 percent of which was carbon-free last year).

Take the Stargate Project, a plan led by OpenAI to invest $500 billion in as many as 20 new data centers over the next four years. One campus alone would sport a 360-megawatt natural gas power plant capable of powering a medium-sized city. (The Washington Post has a content partnership with OpenAI.) The expansion of the two most affordable, accessible sources of new energy — solar and wind — has slowed amid the Trump Administration’s assault on the industries. Plans to restart the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, ignite fusion reactors and drill for geothermal energy remain years (decades?) away from commercialization.

That’s playing out in places like Virginia, home to the world’s largest cluster of data centers, where there’s a scramble to bring new power online, often from fossil fuels. Ratepayers may pay the price in the form of dirtier air and hundreds of dollars in annual utility bills to cover the growth of data center energy costs.

For AI companies, the promise of superintelligence remains too important to slow down. “Intelligence too cheap to meter is well within grasp,” claimed Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI. “As datacenter production gets automated, the cost of intelligence should eventually converge to near the cost of electricity.”

The phrase “too cheap to meter” has had a disappointing past. In a 1954 speech, Lewis Strauss, then the chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, laid out a bright future when nuclear power would be so inexpensive, charging for the electricity it generated would be unnecessary. This day could be “close at hand,” he predicted, “I hope to live to see it.”

The forecast has haunted the nuclear power industry ever since.

Thảo luận

Follow Us

Tin phổ biến