Giữa cơn sốt chip AI, tại sao Singapore vẫn đặt cược vào chip truyền thống?

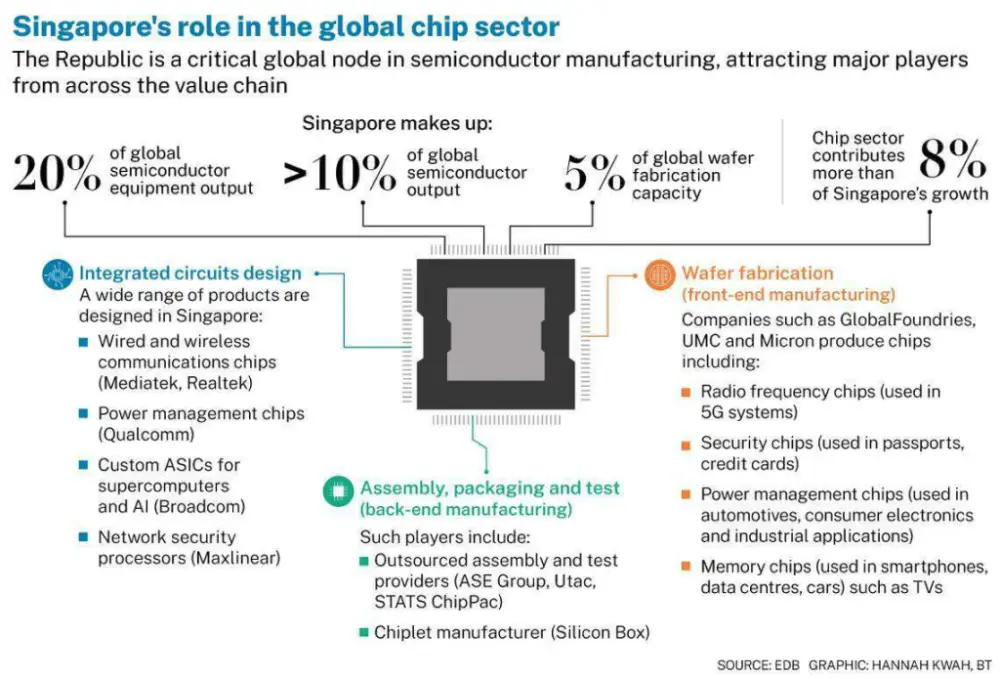

- Giữa cơn sốt toàn cầu về chip AI, Singapore lại tập trung vào sản xuất chip truyền thống (mature-node chips) sử dụng công nghệ từ 28nm trở lên. Những chip này được ứng dụng rộng rãi trong các thiết bị gia dụng, ô tô và máy móc công nghiệp. Ngược lại, chip AI đòi hỏi công nghệ tiên tiến hơn nhiều, từ 7nm trở xuống.

- Hiện tại, chỉ có 3 công ty trên thế giới có khả năng sản xuất chip AI là TSMC (Đài Loan), Samsung (Hàn Quốc) và Intel (Mỹ). TSMC đang thống trị thị trường với 90-95% thị phần. Trong khi đó, Hàn Quốc lại nổi trội ở mảng sản xuất chip nhớ băng thông cao, một thành phần quan trọng để huấn luyện các mô hình AI.

- Singapore không sở hữu bất kỳ cơ sở sản xuất chip tiên tiến nào. Rào cản gia nhập rất lớn do chi phí đầu tư đắt đỏ. Một chiếc máy quang khắc cực tím (EUV) để sản xuất chip dưới 7nm có giá lên tới 180 triệu USD, chưa kể chi phí bảo trì hàng năm. Các nước phát triển lớn như Mỹ và Nhật Bản đang tung ra các gói trợ cấp trị giá hàng tỷ USD để cạnh tranh giành các nhà sản xuất chip hàng đầu như TSMC.

- Tuy nhiên, nhu cầu về chip truyền thống được dự báo sẽ vẫn rất lớn và ổn định trong dài hạn. Bởi lẽ, chúng được ứng dụng trong vô vàn lĩnh vực từ cơ sở dữ liệu, mạng viễn thông, tự động hóa nhà máy, cho tới ô tô thông minh, điện thoại và máy tính xách tay. Sự phát triển của AI cũng sẽ kéo theo nhu cầu tăng cao về năng lực tính toán, lưu trữ và truyền tải dữ liệu.

- Lợi thế của chip truyền thống là có một lượng khách hàng rất đa dạng. Ngoài ra, chúng cũng ít chịu ảnh hưởng từ các căng thẳng địa chính trị vốn đang bao trùm lĩnh vực chip AI.

- Thay vì cố gắng chen chân vào thị trường chip AI, Singapore hoàn toàn có thể tận dụng thế mạnh sẵn có của mình trong lĩnh vực sản xuất chip truyền thống. Đây là lợi thế mà Singapore đã gây dựng từ những năm 1960-1970, khi các tập đoàn bán dẫn lớn bắt đầu đặt chân vào đảo quốc này.

- Hiện nay, nhiều ông lớn như GlobalFoundries, Micron, STMicroelectronics đang vận hành các nhà máy sản xuất chip tại Singapore. Họ có xu hướng mở rộng các cơ sở hiện tại thay vì xây dựng nhà máy mới ở nơi khác, nhằm tiết kiệm thời gian cho việc kiểm định và đáp ứng các tiêu chuẩn của khách hàng.

- Tháng 6/2023, liên doanh giữa NXP Semiconductors và Vanguard International Semiconductor Corp đã công bố kế hoạch đầu tư 7,8 tỷ USD để xây dựng một nhà máy chip tại Singapore. Nhà máy này sẽ sản xuất chip 40-130nm cho thị trường ô tô, công nghiệp, tiêu dùng và di động.

- Bên cạnh đó, số lượng sinh viên tốt nghiệp ngành vi điện tử tại các trường đại học ở Singapore cũng đang tăng lên đáng kể. Chẳng hạn, khoa Thiết kế mạch tích hợp của ĐH Công nghệ Nanyang trước đây chỉ có 25-30 sinh viên tốt nghiệp mỗi năm, nhưng con số này hiện đã lên tới 80 người. Sự quan tâm của giới trẻ một phần đến từ sự chú ý mà ngành bán dẫn nhận được trong đại dịch Covid-19.

- Khi năng lực của ngành bán dẫn Singapore được cải thiện, cơ hội việc làm cũng gia tăng. Các công ty thiết kế chip như AMD đang chuyển nhiều hoạt động thiết kế chip cao cấp sang Singapore, tạo điều kiện cho sinh viên tốt nghiệp thăng tiến. Để thu hút nhân tài, AMD cũng đang trả mức lương cạnh tranh hơn, thu hẹp khoảng cách với thung lũng Silicon.

- Chính sách mở cửa và chào đón nhân tài nước ngoài của Singapore cũng là một lợi thế quan trọng. Bởi không phải tất cả nhân lực cần thiết cho ngành bán dẫn đều có thể được đào tạo trong nước. Những yếu tố như an toàn và việc sử dụng tiếng Anh phổ biến đã giúp Singapore trở thành điểm đến hấp dẫn với nhân tài nước ngoài.

- Kinh nghiệm của Hàn Quốc và Đài Loan cho thấy việc thu hút nhân tài bán dẫn giàu kinh nghiệm từ bên ngoài đóng vai trò quan trọng cho sự phát triển của ngành. Ngược lại, Nhật Bản đã tự hạn chế trao đổi nhân lực từ 30 năm trước, dẫn tới sự chậm lại trong phát triển ngành bán dẫn.

📌 Trong khi nhiều quốc gia đang chạy đua sản xuất chip AI, Singapore vẫn kiên định với lộ trình phát triển chip truyền thống vốn là thế mạnh của mình. Thị trường chip truyền thống có quy mô rất lớn, ổn định và ít bị ảnh hưởng bởi căng thẳng địa chính trị. Với hệ sinh thái bán dẫn đã phát triển qua nhiều thập kỷ, nguồn nhân lực được đào tạo bài bản và chính sách mở cửa với nhân tài nước ngoài, Singapore hoàn toàn có thể tận dụng cơ hội từ nhu cầu chip truyền thống gia tăng do sự bùng nổ của AI. Trong 5 năm tới, Singapore được kỳ vọng sẽ thu hút thêm 10-15 tỷ USD vốn FDI vào lĩnh vực bán dẫn.

https://www.techinasia.com/singapore-losing-out-ai-chip-boom

Is Singapore losing out on the AI chip boom?

Co-written by Sharon See

The global AI boom is spurring some countries to vie for dominance in making leading-edge microchips – but not Singapore.

The city-state’s focus on “mature-node chips” – used in appliances, cars, and industrial equipment – means its semiconductor ecosystem may have limited exposure to the AI boom, says Maybank economist Brian Lee.

Yet industry watchers do not see this as a concern, as the market for mature-node chips is much larger than that for leading-edge ones.

The chips that Singapore makes are for the mass market, says Ang Wee Seng, executive director of the Singapore Semiconductor Industry Association (SSIA).

No appetite for AI chips

AI chips are made to provide high computing power and responsive speed, says Tilly Zhang, a China technology analyst from Gavekal Research.

In contrast to mature-node chips that use so-called “process node” technology of 28 nanometers (nm) or more, cutting-edge AI chips have process nodes of 7 nm or less, and thus require specialized production methods. Current research focuses on developing 2 nm to 3 nm chips.

“That’s something that Singapore will not produce because first and foremost, we don’t have the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography in our fabs here – none of them have that technology,” says Ang, referring to the manufacturing technology for these smaller chips.

Taiwan and South Korea dominate the global AI chip supply as only three companies in the world have the required capability to produce them: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), Samsung, and Intel.

Cost is a major hurdle. There is only one maker of EUV lithography machines and its products cost US$180 million each, excluding yearly maintenance costs, according to Trendforce.

The high barrier to entry is why most chips optimized for AI are made by Taiwan-headquartered TSMC, which is considered more mature, advanced, and reliable than Samsung, said Zhang. She estimates TSMC’s market share to be about 90% to 95%.

However, South Korea shines in producing memory chips, including advanced high-bandwidth chips that also require lower process node capabilities and are essential for AI model training.

Singapore, on the other hand, has no advanced chip facilities.

“If other advanced foundries like TSMC or Samsung consider relocating a part of their capacity to Singapore, it could be possible to establish some domestic advanced chip capacity,” Zhang points out.

But with intense competition to woo such chipmakers, industry watchers say that attracting them would be exorbitant.

“More recently, large developed countries like Japan and the US have been dangling very large subsidies in the tune of billions to attract chip production by heavyweights such as TSMC,” Maybank’s Lee points out. “Singapore cannot compete in this subsidies arms race over the longer term.”

Ultimately, companies are the ones making commercial decisions on whether fabs in Singapore should pivot to leading-edge chips, says SSIA’s Ang.

Indirect opportunities

In the “very narrow context” of chip manufacturing, Singapore’s semiconductor industry may not directly benefit from the AI boom, says Ang.

“But if you look at the ecosystem as a whole, from the design, to the packaging and everything else, I think Singapore plays a bigger role than what we actually expect,” he points out.

Ang adds that there is also a trickle-down effect of AI demand: AI requires more computing power, more memory space for databases, and faster connectivity speeds for high-volume data transmission.

The chips that make this possible – by powering databases and communication networks – will continue to be mature-node chips, says Lee Bo Han, partner for R&D and incentives advisory at KPMG in Singapore. In other words, the market for mature-node chips should have ample opportunities and stable demand in the long run.

“Mature-node [chips are] something that we will have to keep using,” he says, citing applications such as factory automation, smart cars, mobile phones, and laptops.

Frederic Neumann, HSBC’s chief Asia economist, agrees that AI chips may not be worth pursuing for Singapore. “Since leading-edge logic chips are hard to manufacture, the technology evolves quickly, and the capital outlays are substantial, it might be worthwhile to focus on other areas of AI-related hardware and software,” he says.

“One opportunity lies in further building on Singapore’s existing expertise in memory chips, including 3D Nand where it holds a roughly 10% global production share,” Neumann adds.

One advantage of mature-node chips is that their wide range of uses means a diversity of clients. Another is that such chips are not affected by the geopolitical tensions surrounding AI-optimized chips.

“If you are in the AI leading-edge technology node, I think you’ll have to be very clear [that your tech] will not end up in China, [as] there is a lot of concern from countries like the US,” says Ang.

Decades of advantage

Instead of trying to go into leading-edge chips, Singapore can hone its established advantage in traditional chips.

This edge has been in the making since the 1960s and 1970s, with the entry of global semiconductor assembly and test operators, also known as “back-end” players.

Now, front-end multinational corporations such as GlobalFoundries, Micron, and STMicroelectronics produce chips that are used in everything from cars to chargers.

As these companies have a strong presence in Singapore, they are more likely to expand their current footprint than build new plants elsewhere, says Ang.

New plants must undergo “qualification,” or ensuring they meet clients’ specifications; expanding an existing plant removes this need and saves time, he notes.

For example, GlobalFoundries took about two years to open the latest expansion of its Fab 7 in Singapore’s Woodlands district. In contrast, TSMC’s second factory in Arizona was announced in 2022, but it may not start production until 2027 or 2028.

Singapore’s continued attractiveness can be seen in the new investments that are still being made.

In June, NXP Semiconductors and TSMC-backed Vanguard International Semiconductor Corp announced a US$7.8 billion joint venture for a Singapore plant that will make 40 to 130 nm chips for the automotive, industrial, consumer, and mobile market segments.

Losing and winning

Though Singapore retains its front-end advantage, its back-end industry has admittedly shrunk. Many such players have moved to cheaper pastures.

When John Nelson joined assembly and test services provider Utac as group chief executive 12 years ago, the company was already moving some of its more manual and technologically dated operations to Thailand.

But instead of leaving entirely, Utac’s Singapore focus has shifted toward research and development.

In September 2020, Utac acquired Powertech Technology Singapore to gain its expertise in a process called wafer bumping. Utac then conducted further engineering R&D to integrate Powertech’s operations post-acquisition.

“You can’t get comfortable, you have to be looking at new things … how can we be successful in each of our operations?” says Nelson.

Even in the mature-node field, innovation is possible. Singapore-based precision manufacturer Jade Micron has seen improvements not just in wafer fabrication, but in areas such as testing. For instance, a single testing machine used to test just two chips at a time, but it can now test up to 32 chips in parallel.

Attracting talent

Singapore’s efforts to maintain its semiconductor edge may be helped by an increasing supply of local talent.

Nanyang Technological University, for instance, has seen rising interest in microelectronics, says SSIA’s Ang. Its integrated circuit design course used to have just 25 to 30 graduates each year, but now has about 80.

He attributes this to the attention that the industry received during the Covid-19 pandemic, when there was a boom in semiconductor demand.

As Singapore’s semiconductor capabilities improve, so do job opportunities. Chip design companies are making higher-end designs here, allowing graduates to move up the value chain.

Such companies include AMD, which acquired high-end chip designer Xilinx in 2022. Together, they have about 1,200 employees in Singapore, including AMD’s chief technology office with some 12 to 15 doctorate holders.

While Singapore does not manufacture AI-related chips, local designers of such chips can expect higher pay, says Steven Fong, AMD’s corporate vice president for Asia Pacific and Japan embedded business.

“The most lucrative, highest paid [engineers] are in Silicon Valley … but we are moving up very fast to narrow the gap with Silicon Valley because of the talent crunch,” he adds.

Singapore’s openness to global talent is also an important edge, says Fong, since not all the required talent for semiconductor R&D can be found locally.

Overseas talent, in turn, are willing to head here, thanks to factors such as the widespread use of English and the country’s relative safety, he points out.

Han Byung Joon, co-founder and CEO of semiconductor startup Silicon Box, notes that Singapore’s openness to foreign talent can help it build a stronger local base.

Markets such as South Korea and Taiwan made great progress partly due to an influx of experienced semiconductor talent, he points out. In contrast, Japan stopped such talent exchanges about 30 years ago and became more self-sufficient, which led development to slow.

“If you have openness and bring in people who are trained and experienced somewhere else … you will be successful. If you close down the country, then you tend to minimize that opportunity,” says Han.

Thảo luận

Follow Us

Tin phổ biến