Trung Quốc áp đặt kiểm soát xuất khẩu đất hiếm để đáp trả thuế quan của ông Trump

-

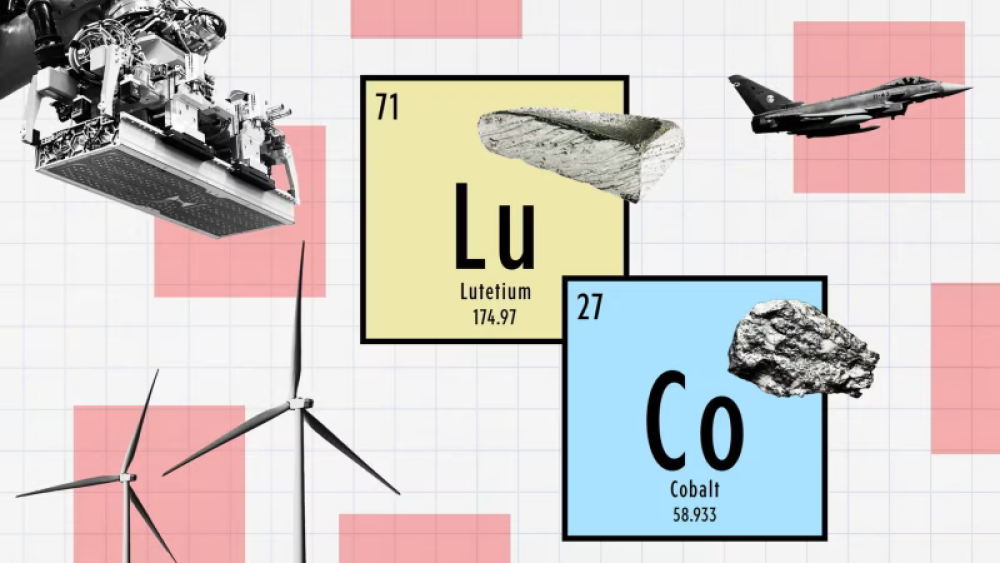

Cuộc chiến thương mại giữa Mỹ và Trung Quốc dưới thời Donald Trump đã làm bùng phát cuộc đua kiểm soát khoáng sản chiến lược — yếu tố then chốt cho xe điện, điện thoại, thiết bị quân sự và năng lượng sạch.

-

Sau khi Mỹ áp thuế trừng phạt, Trung Quốc đáp trả bằng cách kiểm soát xuất khẩu đất hiếm, đặc biệt các nguyên tố mà họ gần như độc quyền như dysprosium, terbium, yttrium.

-

Động thái này nhằm gây "tác động tối đa" lên chuỗi cung ứng quốc phòng Mỹ, theo chuyên gia Thomas Kruemmer, vì đất hiếm là thành phần quan trọng trong nam châm vĩnh cửu, laser và bộ chuyển hóa xúc tác.

-

Trung Quốc kiểm soát 30/44 khoáng sản chiến lược toàn cầu, chủ yếu ở khâu tinh luyện và chế biến – giai đoạn mà phương Tây yếu thế.

-

Các khoáng sản có rủi ro cung ứng cao gồm: gallium (cho chất bán dẫn, kính nhìn đêm), cobalt (pin và hàng không vũ trụ), và neodymium (nam châm vĩnh cửu).

-

Mỹ và EU được cho là "đã ngủ quên trên tay lái" khi để Trung Quốc vượt mặt nhờ đầu tư bài bản trong chế biến và xây dựng chuỗi cung ứng nội địa.

-

Trung Quốc không hoàn toàn tự túc: nước này nhập đất hiếm nặng từ Myanmar và kim loại quý như bạch kim từ Nam Phi, nhưng bù lại bằng việc đầu tư lớn vào khai thác tại châu Á, châu Phi và Mỹ Latinh.

-

Mỹ khó có thể thay thế nguồn cung Trung Quốc trong ngắn hạn do thời gian dài cho nghiên cứu, cấp phép và xây dựng cơ sở hạ tầng khai thác – mất từ 2 năm trở lên.

-

Giá cao có thể thúc đẩy đầu tư, nhưng Trung Quốc vẫn có thể làm sụp giá thị trường bằng cách tăng sản lượng – khiến nhà đầu tư phương Tây do dự.

-

Các chuyên gia cảnh báo, dù Mỹ muốn đa dạng hóa, việc căng thẳng với Canada – cường quốc khoáng sản – và thiếu chính sách hỗ trợ lâu dài có thể phá hỏng nỗ lực tự chủ.

-

Chính sách thương mại của ông Trump được đánh giá là "tự làm khó mình" vì tạo hiệu ứng ngược và làm tổn thương cả đối tác lẫn doanh nghiệp trong nước.

📌 Cuộc chiến khoáng sản chiến lược giữa Mỹ và Trung Quốc leo thang khi Trung Quốc kiểm soát xuất khẩu đất hiếm, đe dọa chuỗi cung ứng công nghệ cao. Trung Quốc dẫn đầu tinh luyện 30/44 khoáng sản quan trọng, trong khi Mỹ cần 2 năm trở lên để đa dạng hóa nguồn cung. Các chuyên gia cảnh báo phương Tây đã mất thế chủ động vì thiếu đầu tư và chiến lược dài hạn.

https://www.ft.com/content/aa03e3b0-606d-4106-97dc-bac8ad679131

#FT

How critical minerals became a flash point in US-China trade war

Beijing’s response to Donald Trump’s tariffs intensifies battle to control supply of commodities vital to high-tech sectors

Apr 24 2025

Donald Trump’s trade war with China has intensified the battle to control the market for critical minerals that are essential in products ranging from electric vehicles to iPhones and military hardware — and underscored Beijing’s dominant position in it.

China’s response to the US president’s punitive tariffs was to introduce controls on the export of a group of elements in the rare earths category, sparking fear in the western companies, such as US carmakers, that rely on them. Trump hit back by ordering a probe into the security risks posed by American reliance on imported critical minerals — a process that typically results in sweeping tariffs.

The stand-off threatens to undercut years of efforts to build up the complex yet fragile supply chains in critical minerals that stretch across the globe, and the challenge faced by the west to break free from China’s stranglehold.

What are critical minerals and rare earths?

Critical minerals traditionally referred to commodities such as tin, nickel and cobalt that were vital to the defence sector.

But an expanding pool of materials are now labelled as critical because of their importance in a range of high-tech industries including clean energy, semiconductors and other advanced technologies, and the higher risk of supply disruptions because the extraction or processing is dominated by a single country — in many cases, China.

The EU has designated more than 30 due to their economic importance and supply risk, while Trump’s executive order applied to a wider list of about 50, including zinc and lithium.

Rare earths such as dysprosium, terbium and yttrium are a smaller group of 17 elements that — despite their name — are fairly abundant, although they are often hard to extract because of their low concentrations. They also tend to be bundled together, making it challenging and costly to separate one from another.

The magnetic, luminescent and catalytic properties of rare earths make them indispensable for the powerful magnets used in motors, wind turbines and electronics, as well as the lasers used in missiles and catalytic converters.

Why are they so important?

Just as coal helped to underpin the British empire and the US rose to supremacy on a foundation of abundant fossil fuels, the battle to control the supply of critical minerals is a new frontier.

Modern technologies such as semiconductors, drones and electric vehicles rely on critical minerals, and dominance in these sectors will increasingly define global economic and military superiority.

The decision by China, which has spent years building its market position, to move to a system of licences to control rare earth flows has the potential to be hugely disruptive, experts say, although it remains unclear how it will play out in practice.

Thomas Kruemmer, author of the Rare Earth Observer blog, said the rare earths on China’s restricted list were those where Beijing had almost complete dominance, chosen “to have a maximum impact on the American military-industrial complex”.

One question as the new licensing regime works out is the extent of the stockpiles held by western countries and companies. Holding multiple years of inventory for critical minerals is not unheard of, as quantities can be small.

Ionut Lazar, a consultant at commodities analysis group CRU, said it would take two months for the effects of the restrictions to feed through to users, putting a range of industries on tenterhooks.

Where is China most dominant?

China is by far the main player across the critical minerals sector, but its grip is often strongest over the so-called midstream — the refining and processing of the metals — than over the mining itself.

David Merriman, research director at the Project Blue consultancy, said Beijing had applied export restrictions on the particular rare earths it targeted because it had the “greatest control over the global supply for these elements”, giving the potential for maximum disruption.

As well as being a negotiating tactic in the escalating Sino-US trade war, the move will help protect China’s domestic magnet manufacturers while undermining US competitiveness in EVs, electronics and computing, said Merriman.

The US Geological Survey said in March that China led production of 30 of 44 critical minerals, from arsenic to tungsten. In an earlier study, it said the materials thought to have the highest supply risk were gallium, vital for semiconductors and night-vision goggles; cobalt, an aerospace and battery metal; and neodymium, a “light” rare earth used in permanent magnets.

Sir Mick Davis, the former Xstrata chief who leads Vision Blue Resources, a critical minerals investor, told a conference in Washington this month that Beijing had a strategic and competitive edge because of its investments in processing within its own borders.

“The west, Europe, the US have been asleep at the wheel watching this happen,” he said.

Who does Beijing still rely on?

This depends on the mineral. In some cases, China is almost self-sufficient. For example, China mined more than three-quarters of the world’s graphite in 2023, the main material used in a battery’s anode.

But Beijing has also invested heavily to secure supplies of mineral resources overseas, sometimes in return for infrastructure investment.

It has increased its reliance on neighbouring Myanmar for heavy rare earths, as domestic resources have fallen but it still needs feedstock to go into its separating and refining plants.

South Africa supplies precious metals such as the platinum and rhodium used in catalytic converters and hydrogen fuel cells, led by Anglo American Platinum.

Chinese groups Zijin Mining, Huayou Cobalt and CMOC have also bought up mines in Asia, Africa and Latin America that yield lithium, nickel and cobalt, all important battery metals.

Can the US secure alternative supplies?

Building up the critical minerals infrastructure to allow the US to bypass China would takes years, as companies would have to go through lengthy research phases, permitting processes and construction.

Yet market disruptions and higher prices could end up being good for diversifying supply chains, because new mines and processing facilities would be more investable at higher prices.

“This is not straightforward,” said Willis Thomas, head of the consulting arm of the commodities analyst CRU. “It will take two years to sort out any truly tight supply crunch.”

Financiers may hesitate to fund new projects, because China has the ability to collapse prices by lifting production and flooding the market. Another complication is that critical minerals are highly specialised and often made to customer specifications.

Experts believe that long-term government support mechanisms such as concessional financing, as well as stockpiles of raw materials from countries other than China, would be needed to create an independent supply chain.

Yet the US critical minerals probe and the nation’s deteriorating relations with Canada — a minerals superpower — could stymie international efforts to diversify critical minerals supply chains, they warned.

“A lot of what you see from Trump policy is potentially self-defeating,” said Timothy Puko, director of commodities at Eurasia Group, a political risk consultancy. “Especially the ripple effects from how he manages trade.”

Thảo luận

Follow Us

Tin phổ biến