Trung Quốc hay Mỹ đang thắng trong cuộc đua AI? “Hiệu ứng Bắc Kinh” thách thức thế giới

-

Khái niệm “California effect” (1995) và “Brussels effect” (2012) mô tả cách luật nghiêm ngặt ở California và EU thúc đẩy tiêu chuẩn toàn cầu. Năm 2025, một “Beijing effect” mới nổi lên trong quản trị AI.

-

Trước đây, ít ai tin Trung Quốc có thể dẫn đầu trong AI do kiểm soát internet khắt khe và lệnh cấm ChatGPT. Nhưng bước ngoặt diễn ra tháng 1.2025 khi DeepSeek-R1 ra mắt, là mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn (LLM) tiên tiến phát triển với chi phí và năng lực tính toán thấp hơn nhiều so với các đối thủ Mỹ.

-

“DeepSeek moment” đặt dấu hỏi về chiến lược của Mỹ ngăn Trung Quốc tiếp cận chip tiên tiến. Tuy nhiên, DeepSeek bị cấm tại Ý do lo ngại quyền riêng tư và tại Đài Loan vì an ninh.

-

Trung Quốc thúc đẩy AI với nguồn điện rẻ, tuyên truyền tích cực và mục tiêu thương mại “rẻ – nhanh – đủ tốt”. Chiến lược chấp nhận đứng thứ hai sau Mỹ được xem là khôn ngoan và hấp dẫn nhiều quốc gia.

-

Ngược lại, Mỹ coi AI như cuộc chạy đua vũ khí. Tháng 2.2025, Phó tổng thống J.D. Vance chỉ trích châu Âu quá thận trọng, khẳng định “tương lai AI không thể thắng bằng sự lo lắng về an toàn”. Chính quyền Trump cũng đe dọa áp thuế trừng phạt lên các nước muốn siết công ty công nghệ Mỹ.

-

Singapore đưa ra quan điểm cân bằng: AI giống điện hay máy tính – cần thời gian để phổ cập hơn là chỉ chú trọng vào công nghệ tiên phong.

-

Nghiên cứu của Angela Huyue Zhang cho thấy quản trị AI tại Trung Quốc thực dụng hơn suy nghĩ: kiểm soát thông tin chặt, nhưng lỏng lẻo trong quyền riêng tư, dữ liệu, bản quyền, giúp thúc đẩy nhận diện khuôn mặt và chia sẻ dữ liệu nhà nước cho doanh nghiệp.

-

Trung Quốc chấp nhận các hệ thống AI phục vụ kiểm soát xã hội, như giám sát lao động hay nhận diện người Duy Ngô Nhĩ, điều khó chấp nhận ở phương Tây nhưng có thể hấp dẫn tại các thị trường khác.

📌 Cuộc đua AI toàn cầu đang phân cực: Mỹ tập trung vào thống trị và coi AI như vũ khí hạt nhân mới, trong khi Trung Quốc chọn cách phổ cập công nghệ “rẻ – nhanh – đủ tốt”. DeepSeek-R1 chứng minh khả năng cạnh tranh, dù bị cấm tại Ý và Đài Loan. Với điện giá rẻ, dữ liệu nhà nước dồi dào và chiến lược thực dụng, “Hiệu ứng Bắc Kinh” có thể lan rộng sang các quốc gia đang tìm kiếm giải pháp AI giá rẻ thay vì tiêu chuẩn khắt khe kiểu châu Âu.

https://www.economist.com/international/2025/09/02/who-is-winning-in-ai-china-or-america

Who is winning in AI—China or America?

China offers the world a values-free, results-based vision of AI governance

Share

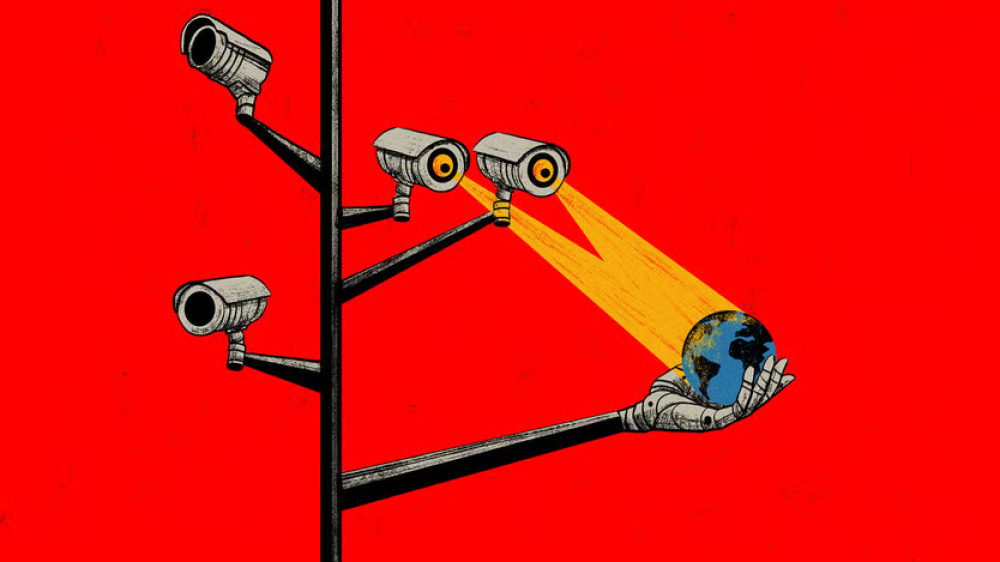

Illustration of a pole with multiple surveillance cameras on it, 2 of them have eyes pointing at a globe being held by a hand coming off the same pole

Photograph: Chloe Cushman

Sep 2nd 2025

|

5 min read

IN 1995, DURING a golden age for globalisation, a business professor from Berkeley coined a cheering term: “the California effect”. When companies in wealthy markets face new competition from foreign rivals, argued David Vogel in his book “Trading Up: Consumer and Environmental Regulation in a Global Economy”, they do not invariably lower standards, as gloomsters might predict. Instead, strict rules in a competitive market can trigger a race to the top, including in neighbouring jurisdictions. A case in point involves strict engine-emissions standards imposed by the state of California, America’s most important car market. Rather than make different engines for different states, to take advantage of those with looser regulations, many firms chose to make all their cars to comply with Californian standards.

In 2012 Anu Bradford of Columbia University coined what she called “the Brussels effect”. This was her tribute to the rule-making superpowers of the European Union, a vast consumer market stitched together by rules written in Brussels. Multinational firms might chafe at fussy EU regulations, or rage when fined by Eurocrats. But time and again, they adopted EU standards worldwide.

Today the global governance of trade is not enjoying a golden age. Still, the largest economies—America, China and the EU—retain a keen interest in setting global standards. And for rule-writers in 2025, shaping AI governance is the greatest prize of all. Until this year few would have bet on a Chinese victory in that contest, or the emergence of a “Beijing effect”. For many countries, the Communist Party’s record of internet regulation set a forbidding precedent. Early glimpses of AI regulation with Chinese characteristics were not encouraging. Authorities swiftly banned ChatGPT, an American generative AI chatbot. The party is especially sensitive about apps that recommend content. In 2023 officials required generative AI services that can shape public opinion to undergo a security assessment and register their algorithms.

China’s reputation for innovation was boosted in January, with the release of DeepSeek-R1, an advanced large-language model produced with a fraction of the computing power and financial support needed by American rivals. The “DeepSeek moment” cast into doubt American government strategies to maintain a lead in AI by denying China access to advanced semiconductors. But technical success faces political obstacles. Italy banned DeepSeek over data-privacy concerns and Taiwan barred DeepSeek from government systems, citing security fears.

For all that, China’s AI investors and officials are upbeat. The state is pouring resources into a drive to produce applications that are cheap, accessible and good enough. With the help of cheap electricity and a domestic propaganda barrage about AI’s benefits, the party wants the technology to be used as quickly and widely as possible. Being content to come a close second to America is seen as a smart commercial bet. It is also an approach likely to resonate with many countries. The contrast with America is stark, where some in Congress compare the race for AI supremacy to the quest to split the atom. In February Vice-President J.D. Vance scolded Europeans for overcautious regulation, declaring: “The AI future is not going to be won by hand-wringing about safety.”

Others seem to share China’s apparent hunch that AI is a general-purpose technology of huge but not apocalyptic significance: something more like electricity or computers than the atom bomb. In July Singapore’s prime minister, Lawrence Wong, reminded an audience of business people that after the electric dynamo was invented, it took decades to find industrial uses for it. “We get very enamoured with countries that are the leaders of the cutting-edge, frontier technology,” said Mr Wong. “But in fact, the big advantage of technology is when there is broad-based adoption.”

What is more, China’s regulation is more pragmatic and industry-friendly than outsiders suppose, argues a paper by Angela Huyue Zhang, a law professor at the University of Southern California. “The Promise and Perils of China’s Regulation of Artificial Intelligence”, published last year, catalogues how strict controls on information co-exist with lax enforcement of rules on privacy, copyright or data protection. Thus, China’s AI facial recognition systems are world-class because officials share reams of government data with private firms. Judges boast publicly of making rulings intended to accelerate China’s AI development.

Social control? There’s an app for that

If a “Beijing effect” ever catches on, it is unlikely to trigger a race to the top. China’s approach puts profitability, convenience and social order ahead of individual rights. A European Commission white paper on AI from 2020 frets about the risks of discrimination by algorithm. It cites facial recognition systems that are less accurate when scanning dark skin, and algorithms that betray racial bias, for instance when predicting whether a known offender will commit another crime. In China, racial discrimination is a business model. Companies have been caught registering patents for systems to spot Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities long subjected to intrusive, human surveillance by Chinese police. The EU white paper worries about employers using AI to track workers’ behaviour. In China, that is a flourishing industry.

China’s version of AI governance faces obstacles in liberal democracies, then. But plenty of other countries are in the market for cheap technologies judged by their performance. China has one more advantage. It is competing with a Trump administration openly bent on AI dominance, and on using that monopoly power to impose its ideological preferences. Mr Trump recently threatened punitive tariffs on foreign countries that seek to regulate American tech firms in ways that he dislikes. Once again, America is handing a political gift to China. Call that the Trump effect.

Thảo luận

Follow Us

Tin phổ biến