Six months ago DeepSeek, a Chinese artificial-intelligence (AI) firm, wowed the world with the v3 model and its successors. For the first time, a country other than America—and one that America had cut off from the supply of top-of-the-range semiconductor chips—was producing open-source models that rivalled those designed in Silicon Valley.

Despite the restrictions, Chinese firms kept training world-beating AI models—Kimi K2, unveiled in July by Moonshot AI, a Beijing-based lab founded by an alumnus of Google and Meta, rose straight to the top of the global leaderboards. With more parameters, as the connections between a model’s artificial neurons are called, than any open-source equivalent, Kimi K2 outperformed its Western rivals ChatGPT 4.1 on tests of coding ability and Claude 4 Opus on tests of science knowledge.

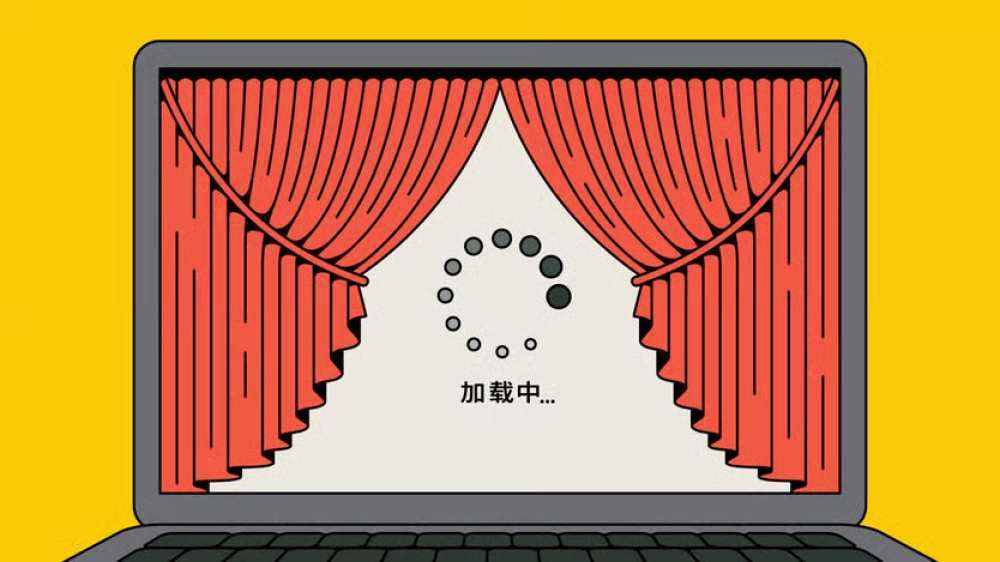

But for models to really impress, they need to be used. This is where chip restrictions have bitten the hardest. Shortages have affected the data centres AI labs need to run their systems once trained. Slowdowns, usage limits and dropped connections are becoming common. “We’ve heard your feedback—Kimi K2 is SLOOOOOOOOOOOOW,” Moonshot posted on X a few days after the launch. DeepSeek, meanwhile, has delayed the launch of its latest AI model to avoid similar performance issues, according to a report from the Information. And so both companies were given cause to celebrate two weeks ago, when the White House reversed its latest export controls, once again allowing Nvidia to sell its H20 chips in China. Making these available to tech companies there will remove the hurdles currently slowing their growth.

China is fertile ground for an AI boom: the country has millions of science and engineering graduates, spare grid capacity, the political will to build data centres as fast as concrete can be poured, and access to all the West’s public data sources and more of its own. It lacks a home-grown source of computing power, however, a fundamental constraint that has so far shaped the development of its industry.

In the past few months Chinese firms have found many ways to work around American restrictions. Banned chips worth $1bn have entered the country since April and domestic companies, such as Huawei, have developed chips to match Nvidia’s top-end offering in some respects (though at smaller volumes). A relentless focus on efficiency has also led to breakthroughs.

Limited access to chips also explains another feature of the Chinese AI sector that has baffled outsiders: the devotion to open-source releases. DeepSeek v3 and Kimi K2 are both available through third-party hosting services such as Hugging Face, based in New York, as well as to download and run on users’ own hardware. That helps ensure that, even if the company lacks the computing power to serve customers directly, support for its models is still available elsewhere. And the open-source releases serve as an end-run around hardware bans: if DeepSeek cannot easily acquire Nvidia chips, Hugging Face can.

Not all Chinese firms have been equally affected by the restrictions. On Friday Alibaba released the latest model in its Qwen 3 family, an open-source reasoning model called Qwen3-235B-A22B-Thinking-2507. The release brings Qwen, and Chinese AI in general, level with not just the best open-source AI models, but the best AI models full stop.

Alibaba’s system is around a quarter the size of K2, requiring commensurately less computing power to run, and, unlike DeepSeek and Moonshot, Alibaba has substantial cloud infrastructure behind it to keep the models working. Making models faster and more efficient to use is clearly the new game in the Chinese AI sector: on Monday another lab, Z.ai, released two models, called GLM-4.5 and 4.5 Air, explicitly touting their speed and efficiency.

But the canny workarounds and impressive models can stretch a resource constraint only so far. And since April, one limitation has bitten harder than any others: the loss of Nvidia’s H20 chips.

Successful AI companies must be able to do two things: train models and then run them, a process known as inference. The best-funded Chinese labs have continued to launch training runs of comparable scale to their Western peers. But inference has proved trickier. Whereas training data centres need monolithic clusters of top-end chips, inference is best performed by chips that balance power, energy efficiency and the ability to move data at speed. Until April, the H20 was the chip of choice.

Worse, while a training run is an upfront expense that can be recouped as revenue over the lifetime of the model, a company that loses money during inference has no opportunity to make it up. That means access to chips for inference, not training, is the bottleneck limiting the growth of China’s AI industry.

In response, the Trump administration has sent mixed signals. Its AI action plan, published in early July, doubled down on some chip controls, emphasising that denying adversaries access to “advanced AI compute” is a matter of both geostrategic competition and national security, and calling for novel approaches to enforcing export controls. At the same time, it has lifted the ban on H20 exports, arguing that it would be better for Chinese AI to rely on American companies for all their technology needs, including inference, than to develop an equivalent domestic capacity.

In the short term, such an easing will be cold comfort to China. Nvidia’s own supply constraints mean it will be unable to meet the country’s demand for chips until the last quarter of the year at the earliest. That means models which lean on efficient output and the ability to run on phones and laptops directly will continue to be prioritised for now. But if American exports pick up once more, then China’s AI sector could, at long last, start 2026 much less constrained. ■