Trung Quốc tận dụng chiến tranh Myanmar để khai thác đất hiếm, đầu độc sông Mekong

-

Myanmar đã trở thành nguồn cung đất hiếm nặng hàng đầu cho Trung Quốc giữa lúc quốc gia Đông Nam Á này bị tàn phá bởi nội chiến, đặc biệt từ sau cuộc đảo chính quân sự năm 2021.

-

Trong khi các nước phương Tây áp đặt lệnh trừng phạt, Trung Quốc vẫn tiếp tục làm ăn với chính quyền quân sự Myanmar cũng như các nhóm vũ trang và dân quân sắc tộc để khai thác tài nguyên, bao gồm cả vàng, gỗ và đất hiếm.

-

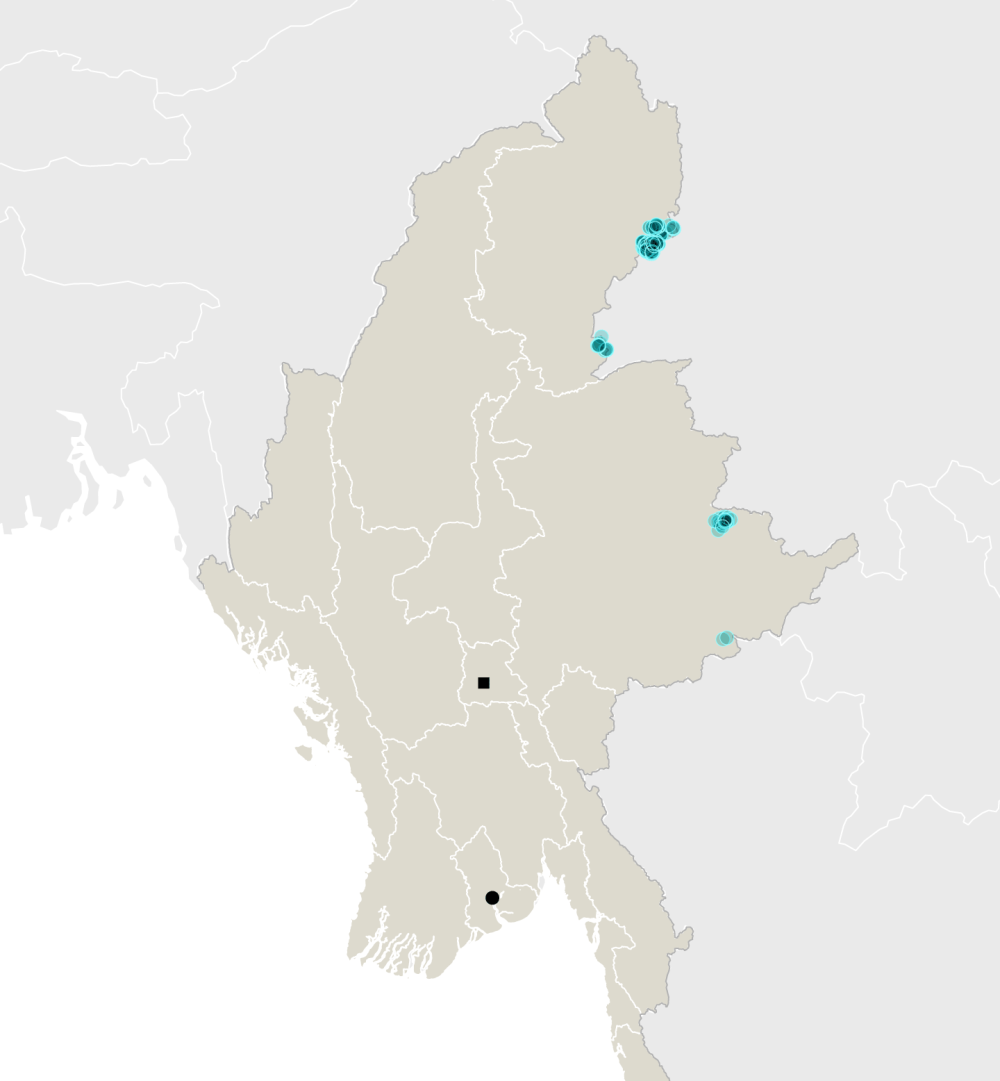

Trung Quốc gửi hóa chất và thiết bị khai thác sang Myanmar, nơi có hơn 300 mỏ đất hiếm tập trung gần biên giới tại các bang Kachin và Shan. Quặng được xử lý sơ bộ rồi chuyển về Trung Quốc để tinh luyện.

-

Các kim loại đất hiếm nặng như terbium và dysprosium – thiết yếu cho điện thoại, ô tô điện và máy móc hiện đại – có trữ lượng dồi dào tại các vùng biên giới Myanmar.

-

Khu vực do nhóm dân tộc thiểu số Wa kiểm soát cũng đang trở thành điểm nóng khai thác, dưới sự bảo trợ không chính thức của Trung Quốc.

-

Quá trình khai thác sử dụng axit ăn mòn để tách quặng, gây hủy hoại nghiêm trọng môi trường: hàng ngàn hecta đất tại bang Kachin đã bị tàn phá.

-

Chất thải độc hại tràn ra sông Kok và các nhánh sông nối với Mekong, gây ảnh hưởng đến sức khỏe người dân Thái Lan như tổn thương da và cá bị biến dạng.

-

Chính phủ Thái Lan đã ghi nhận mức độ kim loại nặng vượt giới hạn an toàn, cho thấy hậu quả lan rộng của khai thác đất hiếm từ Myanmar.

-

Không có quy định lao động hoặc môi trường, khai thác tại Myanmar trở thành cơn sốt vàng mới – mang lại lợi nhuận hàng tỷ USD nhưng để lại cảnh quan bị đầu độc vĩnh viễn.

-

Trung Quốc từng tạm ngừng nhập khẩu đất hiếm từ Myanmar nhằm gây ảnh hưởng lên các phe trong nội chiến, cho thấy vai trò chi phối của Bắc Kinh không chỉ về kinh tế mà còn cả chính trị.

📌 Khai thác đất hiếm tại Myanmar đã bùng nổ nhờ chiến tranh và sự buông lỏng kiểm soát, biến quốc gia này thành nguồn cung chính cho Trung Quốc với hơn 300 mỏ hoạt động. Hậu quả môi trường lan sang Thái Lan khi sông Mekong bị ô nhiễm bởi kim loại nặng, đe dọa hàng chục triệu người phụ thuộc vào dòng sông này.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/11/world/asia/rare-earths-boom-myanmar.html

What to Know About the Rush for Rare Earth Metals in War-Torn Myanmar

In the chaos of war, there’s nothing to stop Chinese firms from ravaging the landscape and extracting the minerals, which end up in China.

By Hannah Beech

July 11, 2025, 1:26 a.m. ET

In minute quantities, the minerals known as heavy rare earth metals are crucial to many of the machines that power modern living, like mobile phones and electric cars. But mining them is often costly, labor-intensive and environmentally destructive. And there is another bottleneck: China controls the refining process.

In recent years, Myanmar, the conflict-torn Southeast Asian nation, has emerged as a leading source of the minerals. Nestled on China’s southwestern flank, Myanmar is fragmented by a civil war that has all but erased labor and environmental regulations. Miners working for Chinese companies have extracted metals worth billions of dollars and shipped them to China.

Now, the toxic byproducts of this mining are gushing out of Myanmar into neighboring Thailand. A stretch of the Mekong River is being poisoned, along with some of its tributaries, heightening fears about the health of one of the world’s great waterways.

Why is this business roaring in Myanmar?

Myanmar’s military, which has ruled the country for more than half a century, staged its latest coup in 2021, ending an experiment with democratic reform. The junta’s brutal response to a pro-democracy movement prompted many Western nations to impose financial sanctions, leaving theregime and its cronies with fewer trading partners.

But China has continued to do business with the generals, who need cash. Various armed groups fighting the military also want to fill their war chests. So do ethnic militias aligned with the army. This situation has allowed Chinese state-owned firms and criminal networks to control rare earth mining and the extraction of other natural resources, like gold and timber, as well as an online scam industry that has defrauded millions of people across the world. A vast illegal economy has blossomed in the chaos of war.

While rare earths were being mined before the coup, some of the areas where it happens have since been fought over by competing forces in the civil war. And China has occasionally throttled rare earth imports from Myanmar to favor one side in the conflict.

Who operates these mines?

Pretty much anyone who can. But Myanmar’s rare earths cannot be mined without Chinese help. Chinese companies have the expertise for extraction, sending chemicals to Myanmar for use in the leaching and basic processing of mineral ores. The rare earths are then trucked across the border to China for further refining.

Much of Myanmar’s mineral bounty is concentrated in the country’s borderlands, such as in the northern states of Kachin and Shan, which neighbor China. Heavy rare earth metals, particularly terbium and dysprosium, are plentiful in this region, and Myanmar in recent years has become the top exporter of these minerals to China, which in turn dominates the refining process.

The frenzy of extraction has now spread to pockets of northeastern Myanmar that are controlled by the Wa ethnic group, which holds autonomous territory under unofficial Chinese patronage.

Why is the mining so destructive?

Heavy rare earths are dispersed widely through the soil, but mining them requires tearing up hillsides and treating them with corrosive acids to leach the ore. Many countries have strict environmental and labor standards to protect the land and the workers. Myanmar today has neither.

Already, in Kachin State, thousands of acres have been destroyed, leaving behind a poisoned landscape and work force. Shan State, where the Wa live, is next.

The environmental toll is now spilling across borders. The Kok River, for instance, flows from Wa-controlled territory into Thailand, where it joins the mighty Mekong. In recent months, residents of Thai villages have complained of skin ailments after contact with the Kok and nearby rivers. Fish have developed unhealthy markings. And Thai government monitors have discovered unsafe levels of heavy metals that are a common byproduct of mining rare earths and other minerals. The long-term health consequences can be serious.

The toxicity has made its way to part of the Mekong, raising fears of yet another threat to a river that nourishes tens of millions of people in different countries. Dams, climate change and deforestation have already endangered the Mekong.

Thảo luận

Follow Us

Tin phổ biến